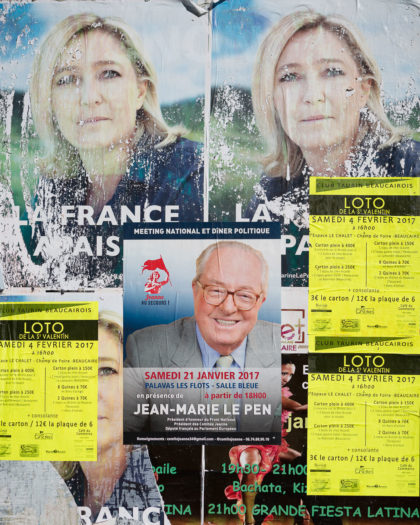

‘The Great Resignation‘, is what journalist Annika Joeres calls it. One of the apparent characteristics of the run-up to the French presidential elections this April is an unprecedented lack of optimism among left-wing voters. It would seem that the light of the socialist party in France is a little dim right now, and many traditional left-wing voters are drifting towards other candidates – or planning not to vote at all. Die Zeit sent Annika and me, as photographer, to investigate the question at a local level, in an unusual little French Riviera town. Contes, in the hills above Nice, is the only municipality in the Maritime Alps whose inhabitants have voted in a communist mayor.

A French Riviera town like no other

Contes, 20 km north of Nice, where the land rises to meet the Alps, is not a Provence postcard town. With its roots in olive oil production, it has never been blessed with fortune or fame. Today, the entrance to Contes is dominated by a cement factory and it isn’t on any South of France tourist maps. Baguettes come cheaper than in nearby Nice, the hillside above the town is suprisingly devoid of swimming pools and it is the first time I’ve found a spot in a carpark on the Côte d’Azur only to realise that the neighbouring vehicle is a burned-out car. The region around Contes has been known as the Red Valley for decades, due to the number of socialist or communist mayors who have administered its villages (see my post about another valley with unconventional politics).

Opting out, off grid

Our first stop was a small, solar-powered wood cabin, perched in a scrubby clearing on the hill above Contes. Philippe Cornejo gave up a career as a cinema projectionist to become a market gardener. Today, he works a 70 hour week to scrape a living from the organic aubergines, tomatoes and other Provence produce that he grows on land loaned to him by the (communist) mayor.

Formerly an ardent leftie, Philippe was quick to tap his chest and point out to us, with some pride, that “the heart beats on the left“. However, the socialist party won’t be able to count on his vote this time. No, Philippe plans to boycott the upcoming election. He had a lot to tell us about his disillusionment with Mr Macron, as well as with the alternative proposed by the current socialist party, and he has had enough of voting tactically to prevent the far right from winning power. The cabin appeared to be entirely devoted to Philippe’s vegetable business and had no lounge (I couldn’t work out where he slept at all, unless it was under the seed tray bench), and we huddled around the stove in the greenhouse as he outlined the reasons why he has chosen to live off-grid, drifting easily into the rather pessimistic extremes of his world view. “Only a catastrophe can save mankind now“, he mused, absent-mindedly wiping mud from the table onto his jeans.

I made three portraits of Philippe. Starting indoors, we then braved the cold to make a portrait among his broad beans – the only plants to be flourishing mid-winter. Yet it was the empty soil in a polytunnel that seemed the most appropriate backdrop to Philippe’s perception of the political left.

Cement factory closure

The reputation that French workers have for not taking things lying down and the strength of France’s trade-unions may have lost their oomph lately, too, if Contes’ story is anything to go by.

The Lafarge cement factory (Lafarge is the world’s largest cement producer) became the most important generator of income in the Red Valley over the last few decades and was, by far, Contes’ biggest employer. Nearly 300 townspeople worked there, digging a giant hole in the mountain and salvaging its grey rock for building materials.

Our next portrait was of Angela Ronca, a former trade union representative at Lafarge. She worked at the cement factory for 22 years, yet this staunch socialist explained how powerless she felt when the corporation decided to shut down the factory, 2 years ago. In the past, Ronca says, workers voted for socialist politicians because they stood up for their jobs. Yet when her factory closed, not a single politician supported the workers – not even Contes’ communist mayor took up the cause of the newly unemployed. Angela, bitterly disappointed, even has reason to believe that her union were paid off to not interfere in the factory closure decision when a lucrative buy-out offer by a rival was refused. Unlike Philippe Cornejo, she will be voting in the national elections this April. However, she will be voting blank, for the first time ever: another loss for the French left.

Last communist standing

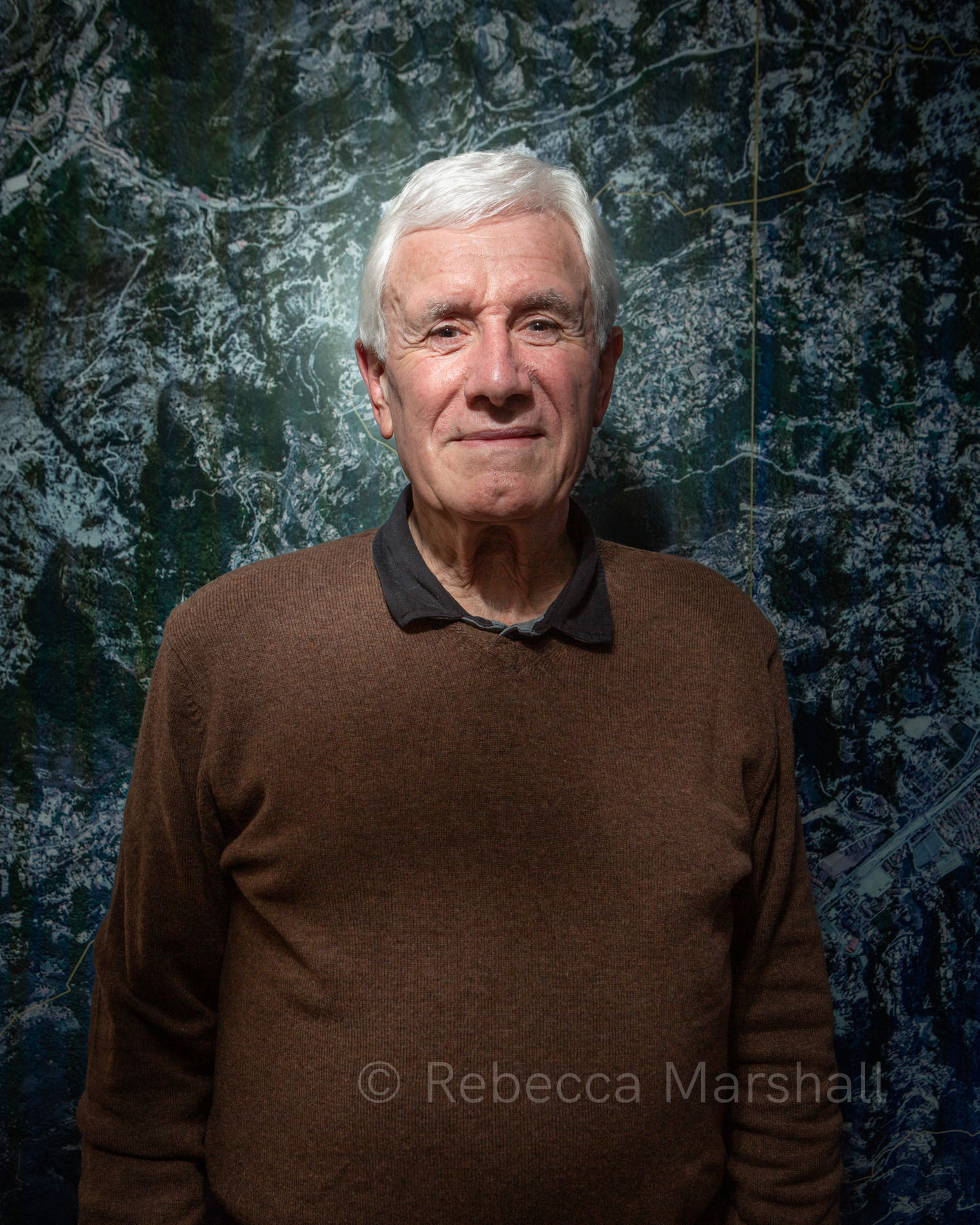

Francis Tujague isn’t giving up though. He has been the mayor of Contes for 25 years, the last to represent the Communist Party in the Maritime Alps. In local elections in 2020, over 80% of the town’s inhabitants voted for him. Francis handed me an extra-large business card and gave me a winning smile as I prepared to make his portrait in front of a satellite image of the Red Valley.

Yet despite its notoriety as the last outpost of communism in the Alpes Maritimes, it appeared to me that there was little to make the Tujague administration a beacon for idealistic, leftist extremists. I guess presiding over a little hilltop town in the South of France doesn’t provide much opportunity to make political earthquakes, but I was slightly disappointed to hear that Francis considers that his best policy for the people of Contes has been to provide free car parks. I was also surprised to learn that many of the same people who voted for him in local elections are likely to vote for far right representatives in upcoming national elections. According to Tujague, “A lot has changed. In the past, the workers used to know that voting for the left meant better wages. But people don’t know what left and right means anymore – they’re politically disorientated”

By the end of the day, I felt more confused about the state of left and right in France than before. However, although Contes may, on the surface, be an exceptional case, I suspect that the underlying disillusionment and contradictions apparent among many of its inhabitants, may turn out to be more representative than one might expect in the upcoming national elections. Watch this space…

> See Reportage portfolio