France is holding its breath. The first round of the presidential election is but a few days away, and it is arguably the most unpredictable one for some time. At the very least, France will see a change of president, and it is likely that he or she will be affiliated to a party that hasn’t governed before. One hot topic for the press is the unprecedented – and, for many, alarming – popularity of the far-right Front National party candidate, Marine Le Pen. Swiss Sunday newspaper NZZ recently sent me to western Provence, to the traditional heartland of le Front National in the South of France. My photographer’s mission? To go boldly forth and make portraits of the men and women who will cast their vote in favour of the ‘FN’ [Front National]…

A rather different south of france

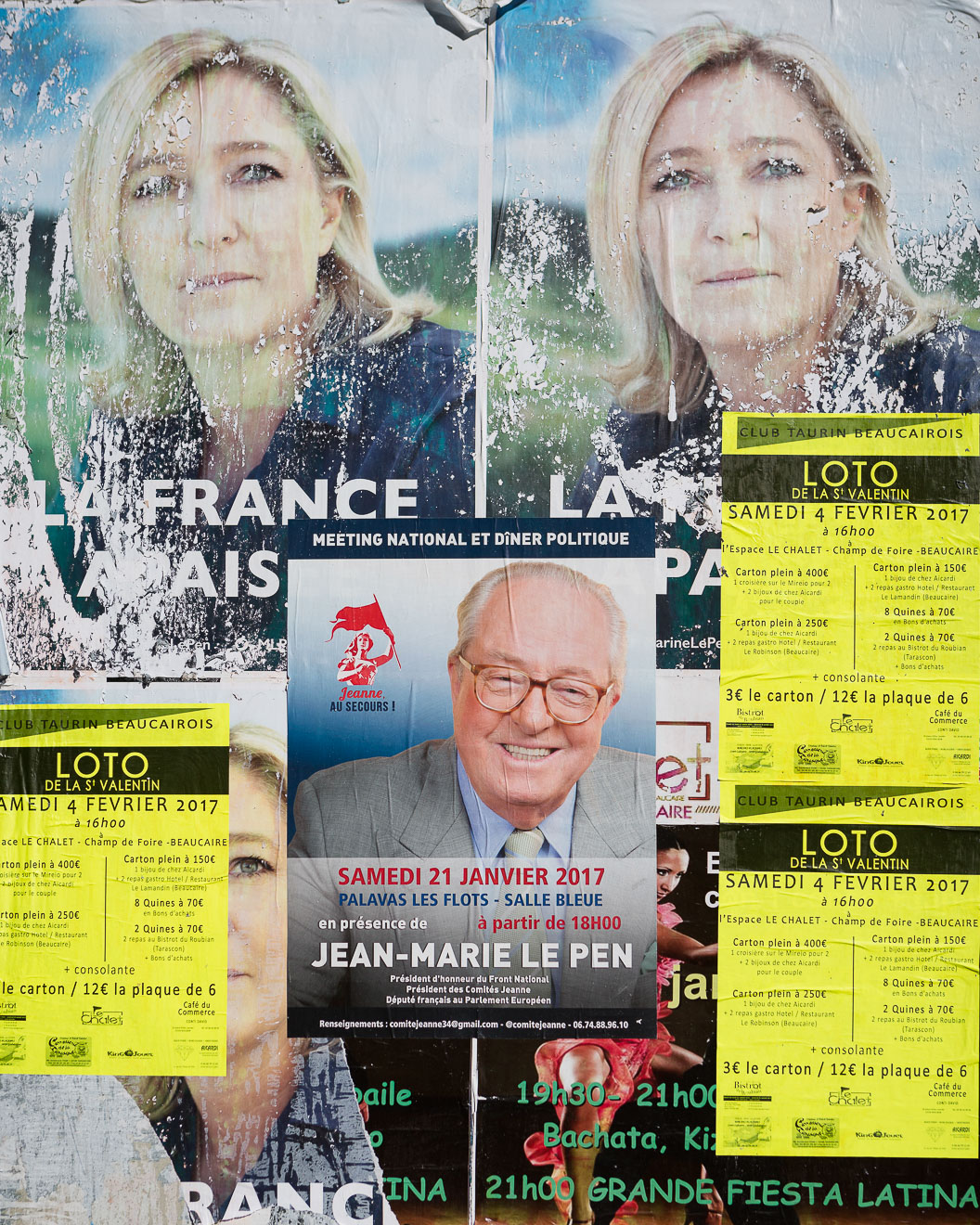

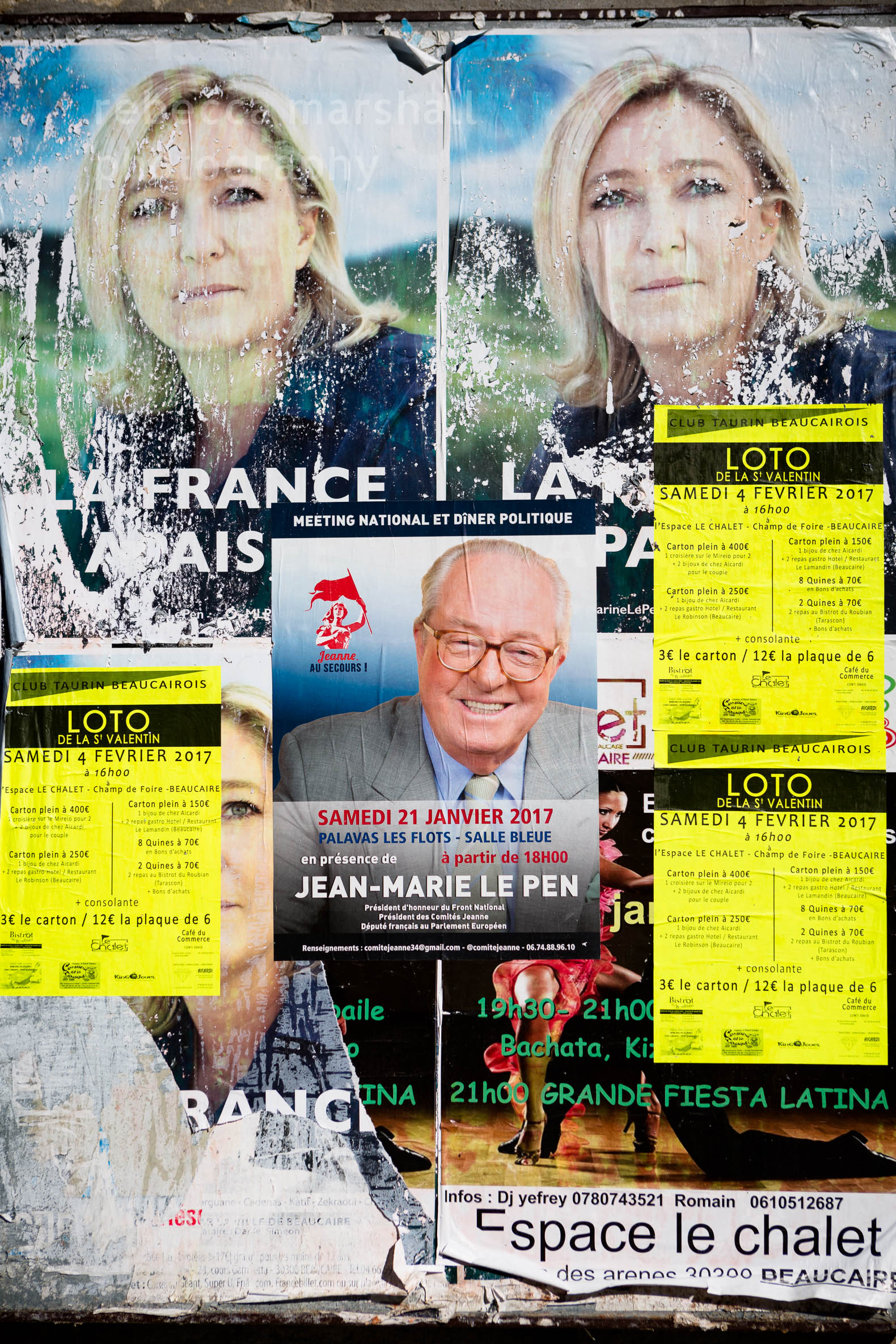

Beaucaire, where I met NZZ’s journalist, is one of the few French towns that has a National Front mayor. A sleepy South of France town, it is, nonetheless, worlds away from the glitzy French Riviera. Its glorious past as a centre of trade (during the 17th century, the annual fair Foire de Beaucaire was the largest commercial event of its kind in the Mediterranean) remains but a dream today. Beaucaire has more than its fair share of boarded-up shops, immigrants (from Spain & Latin America, as well as North Africa) and its wall decorations range from current drug prices scrawled in thick black pen on the walls of the church square to bus shelters daubed with Le Pen’s portrait.

Rue du brexit

Blue-eyed, baby-faced Julien Sanchez has been mayor of Beaucaire since 2014. Some whisper that he is simply a poster boy for the national FN campaign and doesn’t care about ‘his’ town at all. It is true that he doesn’t even live there (it is very unusual for a French mayor not to live locally), and his most famous political action has been to christen a new road ‘la Rue du Brexit‘, which could certainly be viewed as being more about national publicity than local problem-solving. But what do Beaucaire’s own inhabitants think of him, and will these opinions influence their vote in la Présidentielle?

Vox pops failure

When I met the journalist, bright and early in the town square, I was surprised to learn that we had no rendez-vous with FN supporters arranged. She cheerfully told me that she would conduct quick street interviews instead, and take a vox pops approach. As a photographer, my heart sank. Even if, with a bit of luck, we found a few people with the time and inclination to talk about the election, I guessed that taking their portraits would be a different matter. At the best of times, the French tend to be discreet when it comes to discussing political affiliation and voting for the FN (still) carries a degree of controversy. Getting a stranger’s agreement to pose for a full-frontal photograph for a newspaper spread with “I vote FN” printed across it wasn’t going to be an easy ask.

As it was, even talking in this town turned out to be a no-no. Time and time again, at bus stops, on picnic benches and in cafés, friendly faces instantly shut down when we got from “Bonjour” to the matter in hand. By midday, our only willing portrait subject was a tramp who smelled overpoweringly of alcohol. Although by now increasingly dispirited and hesitant, the journalist’s sound Swiss press ethics precluded the tramp’s suitability for interview. A photographer’s job isn’t always about showing up to take the pictures, and in this case I could see that if I didn’t change up a gear, there would be no portraits at all.

No such thing as a free lunch

It didn’t feel pleasant checking out restaurants based on colour of diners’ faces inside, but I figured that our choice of lunch spot would be key, and the writer was only too happy to follow my lead. Sure enough, after a decent steak and lengthy chats about it with the restauranteur and neighbouring diners, we at least started to hear some feedback about the mayor. It seemed that Sanchez IS popular. From what I could work out, this is largely due to his frequentation of local eateries and for arranging town parties (people have particularly fond memories of him comically falling into the canal during one of these). A local leftie, who we spoke to later, said that such activities are emptying the town’s treasury – but the general consensus seemed to be that free wine, free snacks and bringing back traditional boats to the canal is a Good Thing for Beaucaire. The discussions were then steered closer and closer to general National Front policies and, with a whole bunch of willpower and a very full stomach, I soon got my first portrait in the bag.

Restauranteur Nicolas: “If I DID vote for Marine Le Pen, then I wouldn’t tell anyone. Many of the kids I went to school with are Arab, and I just wouldn’t be able to look them in the eye when I go buy cigarettes and bump into them “Why not give her a shot?

If the journalist had expected quick, forthright admissions of “Yes, of course I vote FN” and handy “I’m a racist“-style quotes to go with that, then she didn’t get any. However, “If in theory I Did vote for the FN, then my reasons Might be….” was a general opener, and with a bit of luck the conditional tense was sometimes forgotten as policy details were appreciated and problems expanded upon.

Before the assignment, I had no idea who the typical national front voter is, and I still don’t. One of the things that I appreciate as a photographer, and editorial photographer in particular, is being in a position to see the shades of grey in issues that are so often presented as black and white. I was surprised to learn that far-right Mayor Sanchez is openly gay. I was also surprised to see evidence that the extreme-left and extreme-right are not that far apart (more than one of our few interviewees was in a dilemma as to whether to vote for Le Pen or Mélenchon). Racism is not a simple question either: one of our FN-supporting subjects was an estate agent whose entire rental business depends on foreigners; restauranteur Nicolas has Arab employees and friends he’s known since school; and we talked to an impressively moustachioed retiree who lived for years in Morocco & loved it (he made a point of praising the exemplary Moroccan police approach of beating up young vandals in custody).

Not all FN sympathisers want to leave Europe either: for many, leaving Europe is the only reason Not to vote Front National. The only point that our interviewees had in common seemed to be a lack of belief that today’s mainstream political parties will solve their problems. An apathetic “we’ve tried everything else and it hasn’t worked, so why not give Le Pen a shot?” was a common response.

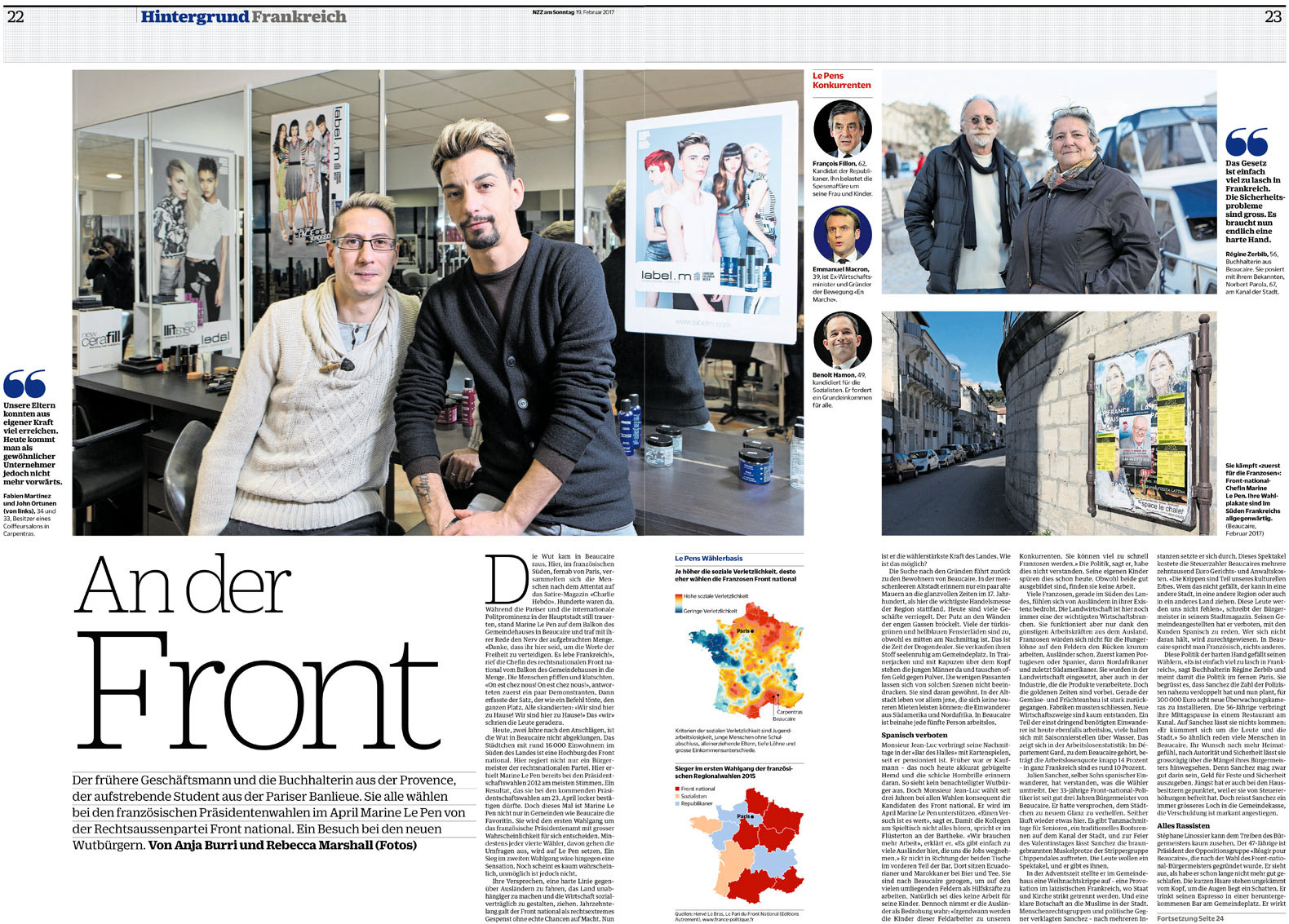

Hard-right hairdressers

It was on the second day, after driving further into the heart of Provence, that we came upon the leading portrait subjects for our feature. Aside from gastronomic fame for its black truffle market, Carpentras is known as the campaign headquarters of Marion Marechal-Le Pen (Marine Le Pen’s niece) and the town also hit the headlines some years ago when many of its Jewish tombs were defaced with swastikas and obscenities. Our attempts at vox pops here were no more successful than in Beaucaire and again, it was the choice of lunch spot and carefully chosen neighbour conversations over food that led us to the goods.

John and Fabien, delightfully camp hairdressers, chattered away with us over a long lunch about the difficulties of being self employed in France, the little disposable income they have, the unfair competition that they face from unskilled immigrant barbers (even though they couldn’t specifically point us in the direction of any such barbershops nearby) and how good the burgers were. While initially reticent, a couple of glasses of rouge later, John and Fabien announced that they would be happy for me to take a portrait of them at their hair salon. I decided to avoid the back wall: a floor-to-ceiling aerial photograph of Manhattan didn’t seem entirely appropriate to the feature. I did, however, find out that this picture, positioned over the sinks, is an important motivational image for John. If all else fails, he confided, he has a simple solution to his problems in France: emigrate to New York.