Every year, the Sunday Times Magazine devotes an entire edition to the Rich List, the definitive directory of the richest people in the world. This year was the guide’s 30th anniversary and the magazine’s picture editor had a billionaire’s portrait to assign to me in Monaco for a Rich List Interview special. I was to photograph Number 48, the founder of easyJet.

First press interview in 10 years

Stelios is one of those rare people who are known by their first name only (which is fortunate, as Sir Stelios Haji-Ioannou is quite a mouthful). I had been told that this interview and editorial portrait would be the first that Stelios, Greek Cypriot son of a shipping magnate, had granted in around 10 years. As founder of the airline that has been a game-changer in world travel, and with a family fortune of nearly £3 billion, he doesn’t really need the PR. In the build-up to the portrait shoot, a steady stream of emails and calls had been flowing between London and the South of France, and Stelios himself was actively involved in these discussions.

One day, I read that Stelios had been assured that the photographer would show him the pictures on a laptop after the shoot. This is an unusual concession for a magazine to make (subjects are not normally involved in the pre-press review of their own portraits), so I assumed that this must be one of the conditions Stelios had set to grant a photographer access to shoot. However, doing it that way just wasn’t going to work for me. I picked up the phone and dialled London. A successful portrait shoot depends greatly on the short, sometimes quite intense, dynamic that occurs between photographer and subject. I want someone to forget the mechanics of their position so that what I capture is more than a pose; it is a presence. If a computer in the corner reminds the person that they will shortly see how they look, the end result is uppermost in their minds. Instead of relating to the photographer fully, they will be focused on their own image, which sets up a distracting tension for me. No, instead, I would send a contact sheet to Stelios that evening, so that he could review the picture set in his own time, setting out his comments by email afterwards.

Suitable spot for a portrait

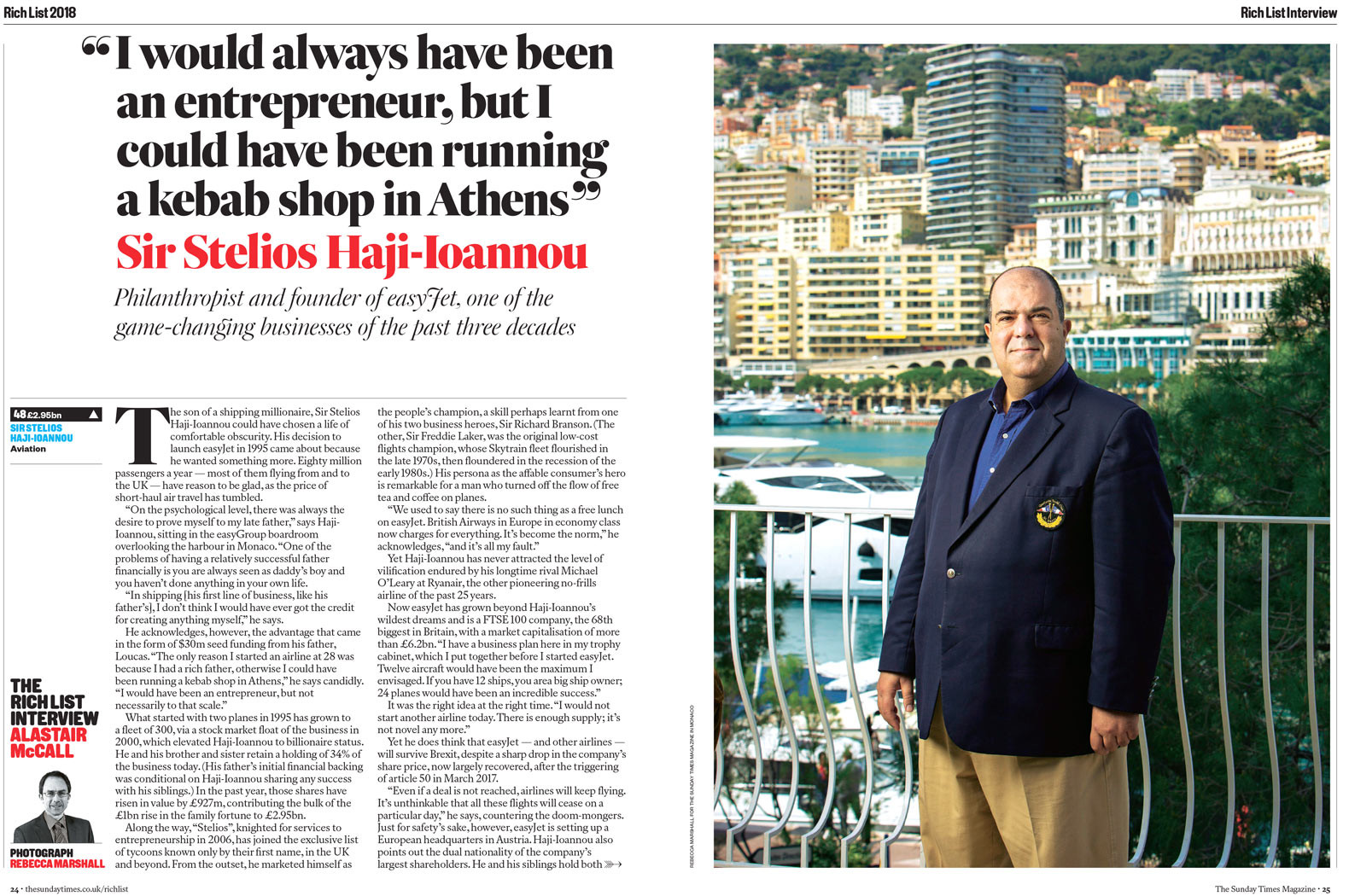

The photo editor had apparently imagined a spacious, impressive billionaire’s office in Monaco when they put together the original photographer brief. I was to take a ‘power portrait’ of Stelios, his feet on a large, shiny desk, a dwarfed model of an easyJet plane in the foreground, or similar. However, Stelios burst that balloon when he sent a snapshot of his (dark, messy and currently-being-renovated) office. I wasn’t surprised: even eye-wateringly expensive real estate in Monaco is often deeply underwhelming. Instead, it was decided that I would work outside on the terrace, using the view of Monte Carlo as a backdrop.

My assistant and I were greeted on arrival by the easyGroup Communications Director, Richard, who’d popped to Monaco from London HQ, and we were shown out onto the terrace. My heart sank: it transpired that not only was Stelios’s office being renovated, the whole building was apparently being done up. The terrace was covered in dust, stacks of old furniture were piled up everywhere and the wall was covered in scaffolding, which obscured the side view onto the harbour. There was only one angle that I could work with, and it was tight. Richard kindly help us to set up the lighting, but he seemed a little ill at ease, and asked me not to make a big deal of the portrait. I didn’t quite know what he meant by “it can’t be fussy for him“, but I felt sure that I could work smoothly with Stelios, from his active involvement thus far.

Trust the photographer

As it transpired, Stelios’s involvement was more active than I’d expected. I guess you don’t create and then continue to head up an international FTSE 100 corporation without a strong sense of control and directorial style, and perhaps this behaviour sticks, even when you’re working with someone who is not an employee. In any case, when he arrived on the terrace and greeted me with a perfunctory handshake, Stelios’s opening line was “how shall we do this?” (and the question didn’t sound as collaborative as the words might look). I explained that, given the light and various restrictions, we had prepared the portrait in the only really workable spot. It was all ready so his time would not be wasted: he could just go straight over there for the final light tests and we could begin. But Stelios didn’t move. He stroked his chin and quietly considered the set-up.

Now I had quickly come to the conclusion that Stelios simply didn’t enjoy being photographed and, sure enough, he hung back. Real trust cannot be established instantly, of course, and I guess Stelios could have no way of knowing that I am honest, but I had assumed that we both knew everyone was on the same page: working to show a flattering portrait of a powerful man. The Sunday Times Magazine and I had no plan to catch him out, to make him look bad or ridiculous. Yet when I alluded to this and said lightly “This will look good, trust me“, his retort was a somewhat conversation-closing: “I don’t“. There is something to be said for blunt honesty, but the kind of negotiation that transpired from that point, before and during the shoot, was not conducive to a free-flowing portrait session.

A question of give and take

In any negotiation, there is some give and there is some take. I’d realised within seconds of meeting Stelios that I’d be giving up the more unusual and creative portrait idea I’d planned to try at the end. The idea of working an easyJet plane into shot, as per the photo editor’s direction, was absolutely NOT going to happen. Even during the safe, conservative portraits that I shot, his sitting down was vetoed (I suppressed a smile remembering the original brief to photograph him with his feet on the desk). I asked “can you place your hand a little further to the left?“; he replied, “No“. Even before he stood in for each set-up, Richard was told to pose in his place so that Stelios could see the image on the camera first (something I’ve never been so insistently asked for, and have rarely conceded during a portrait session). We moved all the kit to shoot extra pictures from a different angle on the terrace too, even though in my opinion the background didn’t work well.

On the ‘take’ side, my own fallback terms were hard won. Stelios did reluctantly agree to move the row of white Stelios Philanthropic Foundation flags on his terrace out of shot. After an early attempt was thwarted, he stood still, instead of jumping out of position after every frame to see the preview on my camera. The first (and published) portrait was made in the place that I had already set up for. And, of course, he didn’t walk out mid-shoot.

Final choice

In the no-man’s land between the magazine’s editorial prerogative to choose what to print and Stelios’s wish (or understanding, it was difficult to tell which) that he would himself select the final portrait, there was rather a lot of room for interpretation. Was he to comment on what he did like or what he didn’t? I knew the magazine required a range of pictures (with varied set-up, format, and expressions) to work with, yet I was prepared to listen if Stelios wished to veto a shot or two, perhaps not including them in the edit. However, by the time my assistant and I had packed up and I went to his office to say goodbye and clarify this, I was greeted with a “What do you want? We’re trying to do some real work now“, and so our exchange was necessarily brief.

Shortly after 06.00 the next morning, Stelios’s comments to the group stated that he had chosen 4 images, although he attached 4 contact sheet pages rather than individual files. Communications Director Richard then offered his (slightly different) opinion in a separate email. A few unanswered calls later, (I was on another assignment), Stelios’s final list of 4 filenames had been circulated (two of which are the photographs you see in this post, selected out of consideration for Stelios’s feelings). Seeing no vetoes, I had of course already sent the full picture set to the magazine. My job was done, and it was for them to make the final choice.

Last weekend, the Rich List finally hit news-stands. Stelios’s full-page portrait, one of only two in the magazine, was prominent. He looked, in my opinion, suitably tanned and mighty. Was this photo on his shortlist? No. Was he happy regardless? I really don’t know. The calls and emails that I’d been receiving from Monaco had at last stopped…