Just east of Monaco and Menton, the French Riviera ends and the Italian Rivera begins. In between these two glittering resorts for people with the means to enjoy them, the area is haunted by those who have no means at all.

The border town of Ventimiglia is the doorway to a better life for the many immigrants who arrive here, most having travelled from Africa, across the Mediterranean and up through Italy. Apart from their train tickets to France, Germany or England, they are unfortunately armed more with hope than appropriate paperwork. In reality, once across the border, sans-papiers are likely to picked up by the police within hours, either on the road or dragged off trains in Menton, Nice or Cannes, then carted straight back to la frontière of France. As photographer, I’ve done a number of assignments on the subject (see a portrait story), but recently the German newspaper Taz asked me to be photographer for a cover feature about the border that offered something new: a positive angle.

We are not the French Riviera

The remote mountain valley of Breil-sur-Roya has something of a history of rebellion. Word has it that the community once tried to make a break for administrative independence from Nice; back in wartime, Jews were harboured there; it is also one rare commune in the South of France to have voted in a left-wing mayor. Now Breil-sur-Roya is rebelling again. In an environment that is increasingly hostile to immigrants, villagers are standing up to the authorities to help those in need.

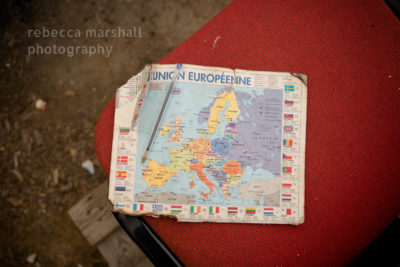

Many of the migrants are asylum-seekers from war-torn Eritrea and Sudan, and a considerable number are unaccompanied minors. On the last leg of a perilous journey, turning back is simply not an option. With the frequent border controls on the coast, some try their luck walking inland, up into the empty mountains. However, they are utterly unprepared: many are still clad in the flip-flops that they left home in, despite the plunging winter temperatures. For those who finally straggle into the village square of Breil-Sur-Roya, 20 kilometres north of Ventimiglia, cold, hunger, dehydration and disorientation are routine.

The new Résistance

There is nothing formal about the support that is offered to new arrivals. No charities, welcome centres or formal organisations are present: just a group of friends. Moved by the immigrants’ plight and angered by what they see as the French government’s inhumane response to the crisis, these residents of Breil-Sur-Roya have welcomed new arrivals into their homes, sheltering and feeding them temporarily. In the past few months, over 20 local people have hosted migrants – and many more have donated food, clothing and supplies.

Visitors generally stay only a few days, they are then helped to continue the next stage of their journeys. A surprisingly well-coordinated ‘humanitarian citizen smuggling’ operation is indeed worthy of WWII résistance acclaim. Over rural roads of the high mountain passes, a convoy of cars communicates by telephone as to whether there are police present, and they cross only when it is safe to get the migrants as far as a bus or train station free of immigration controls. The risks the villagers run are considerable. It is illegal under French law to help illegal migrants enter, travel in France or stay here and those who do so are threatened with up to 5 years in prison and a 30,000 € fine.

All welcome, photographer included

Given the stakes, I was less optimistic as photographer than my journalist colleague Annika about how straightforward the assignment would be. Illegal immigrants are generally reluctant to be photographed and I anticipated that in this case French locals might not want to be identified in the press either. Yet Breil-Sur-Roya appears to stand up fully for what it believes in. After a warm welcome and portrait of the deputy mayor, followed by coffee in the square with two photogenic hosts, Annika and I undertook our own perilous walk along the pavement-less main road and up a steep track to a hillside haven above the village that is becoming increasingly known to the press, both national and international.

Move over Robin Hood. Cédric Herrou, a small-scale olive oil and free-range egg farmer, is developing something of a folk hero reputation. On the terraces above his little stone farmhouse, two caravans, tents and an improvised canopy between olive trees provide a resting place for the needy. His flower-filled garden and the breathtaking views provided a rather incongruous backdrop to the scene that we witnessed.

As chickens scratched around in the dust, 15 weary Eritrean and Sudanese men (women do stay too, but there weren’t any when we visited) were moving quietly around under the oliviers, preparing lunch, airing their bedding and playing cards around a fire. There were no objections to a photographer in their midst, making reportage and taking portraits, and they were happy to tell us their stories (avoiding eye contact as they glossed over certain details – Libya, it seemed, had been a particular source of trauma to some).

Noble law breaker

That afternoon, Cedric had planned to take a number of the underage boys to a gendarmerie for them to be taken into the state’s care, but after some phone calls, he aborted his mission. He says that whether those who have the right to protection in France are dealt with correctly or just driven back to the border in a van and dumped a few kilometres from Ventimiglia, can depend on the mood of the gendarme in charge on the day. Anxious about the wellbeing of his guests, he chooses his moment carefully.

Cédric is not loved by everyone. He goes further than simply sheltering a few sans-papiers: he has picked them up on the streets of Ventimiglia when delivering eggs, to bring them back to Breil-Sur-Roya in his egg van too, and he’s helped well over 250 migrants. While he was voted Azuréen of The Year by readers of local paper Nice Matin, informants also work against him, from railway workers and paramedics he encounters to neighbours in the village. He’s been arrested twice and a current court case, heard since we visited, is pending judgement. “The law is the law” say some – but a caveat does allow aid to illegal migrants if it is given freely. I noticed that even the prosecutor, who calls for an 8 month suspended prison sentence, described Cedric’s actions as ‘noble‘. Watch this space: the verdict will be delivered on 10 February.

As the chill of the afternoon fell in the mountains and the refugees gathered closer around the fire, Annika and I made our way along a shepherd’s path back to the train station. The peace of Breil-Sur-Roya was shattered only a few minutes down the line towards Nice. As the train pulled to a halt in the darkness at Sospel station, a group of armed soldiers and police jumped aboard in a clatter of boots. As they combed the train in their intrusive search for foreigners without permits, I felt a shiver at the reality that the friends of Breil-Sur-Roya face in their résistance.