The humble fig has been by our side since the very beginning. When Adam and Eve erred, it was there to cover up for them (and, despite a headline appearance in the Bible, it displays no particular favouritism for Christians, featuring in the Qur’an too). A recent archaeological discovery suggests that fig trees may have been the world’s first ever domesticated crop (1000 years ahead of wheat), giving us food, medicines and shelter for millennia. Today, our resilient friend might just be stepping up again, to help us out with another of the messes we’ve made: climate change.

Hotting up in the Med

My base in the South of France, with its easy proximity to Italy, Spain and North Africa, makes me a Mediterranean photographer, I guess. I like the feelings of familiarity that I experience when I travel around the region (see my photography assignments in Morocco, Egypt, and my work with Tunisian migrants to Italy) and I’m interested in the issues that connect, rather than divide us, across the Mediterranean Sea. Right now, the impact of global warming is something everyone is experiencing.

A 2°C increase in land temperature throughout the Mediterranean Basin since the Industrial Revolution may not sound like much, but it is a bigger rise than in most places. Climate change scepticism is now surely an impossible position to defend. The past 8 years have been the warmest on record here: droughts, forest fires, dry springs and scorched vegetation are becoming routine. It might be getting tougher being a South of France photographer outdoors in summer temperatures that can now exceed 40°C, but farmers (and wine producers) have it worse. Levels of food production have dropped and Mediterranean harvests are set to suffer even more in the near future.

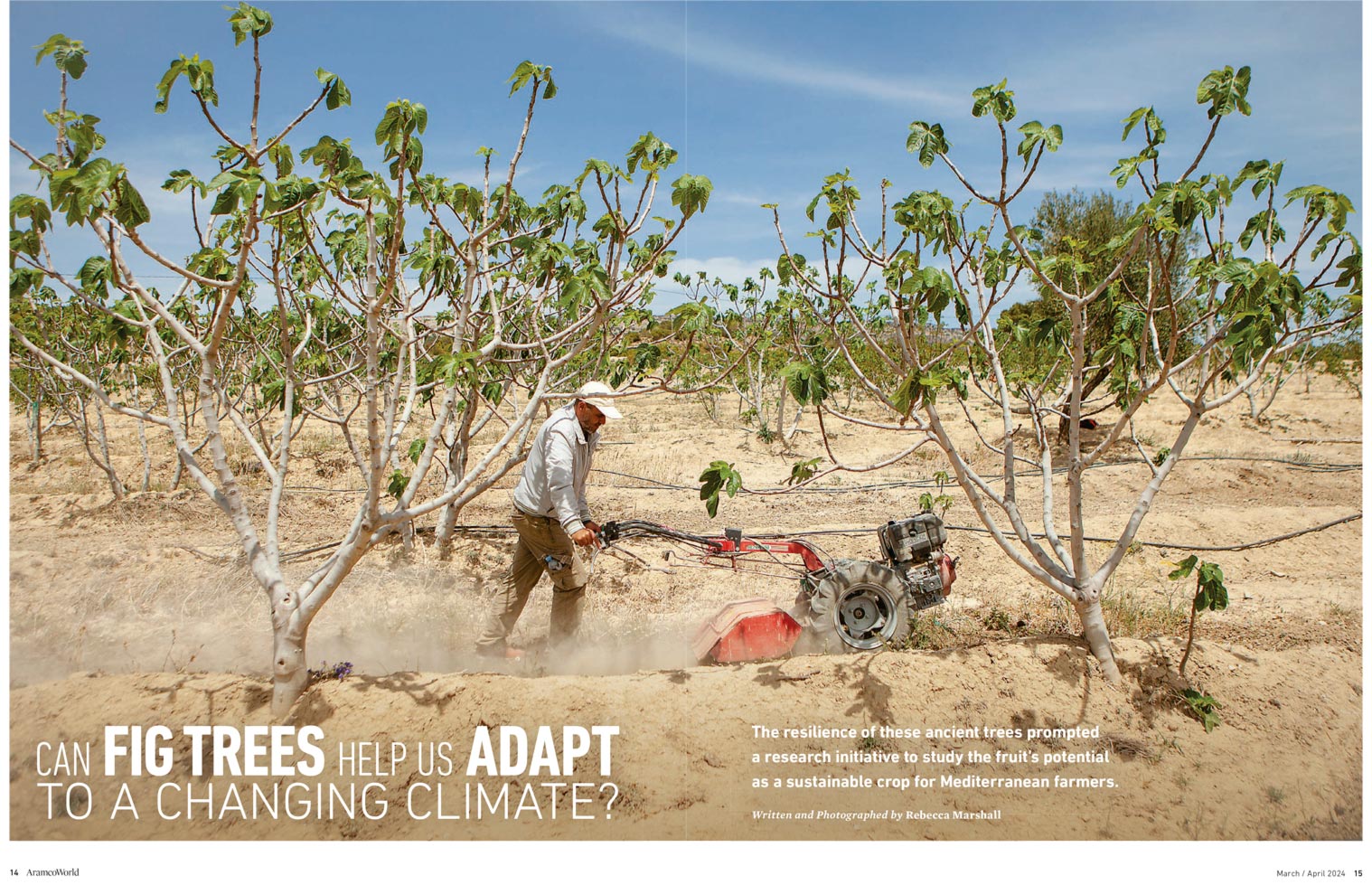

‘The Island of Missing Trees’ is an enchanting work of fiction by Turkish author Elif Shafak, in which part of the narrative is recounted in the first person by a fig tree (which is less weird than it sounds). Reading it, I was struck by the out-of-the-ordinary characteristics that this tree is endowed with, and started cross-checking to see whether the novel’s fig facts were indeed accurate (they were). My winding Google trail led me to the discovery of ‘FIGGEN‘, a ground-breaking, pan-Mediterranean, research initiative, which was investigating the capacity of fig trees to survive in drought conditions, to benefit the region’s farmers. I was hooked. A few months later, I flew from Nice to Tunis, thrilled to meet FIGGEN scientists and visit Tunisia’s main fig-producing regions, as I both wrote and made the photography for a cover feature about fig trees for the 75th edition of Aramco World magazine.

Rock-breaking water warriors

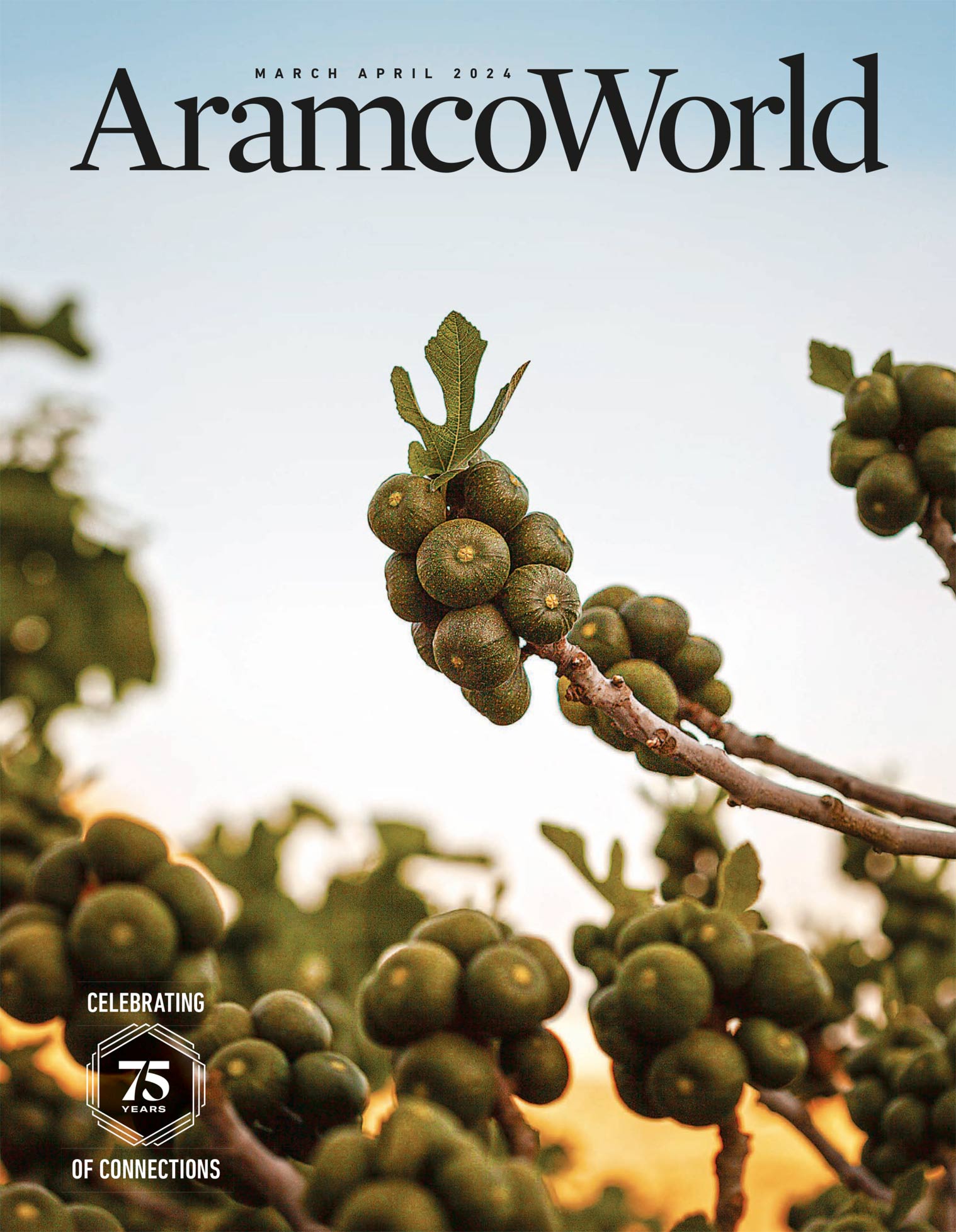

There is nothing common about Ficus carica, better known as the ‘Common Fig’. Figs can grow in places where reaching water seems impossible (in walls of buildings, or on cliffs), and a lack of soil doesn’t put off their formidable, fast-growing roots. They are capable of tearing rocks apart in their hunt for a drink – sometimes, in the process, bringing forth a spring where there was none before. Figs are phoenixes: they can burn in a forest fire, but, unlike olive trees, will grow back quickly the following year. Cut a fig tree down: a new shoot will spring from its stump. These ‘supertrees’ don’t give much credence to fertiliser either; they’re resistant to many pests; and if it gets too hot, their leaves curl up to limit water loss through evaporation – until nightfall, when they open up again.

Despite being the ultimate low-maintenance fruit tree, the fig is disproportionately generous with what it gives, boosting biodiversity in its ecosystem. Fig roots aerate dense, rocky soil (enabling other little beings to move in); their big, fat, mineral-rich leaves provide shade and a cool place to rest when the heat is unbearable; and, when it does rain, ample leaf cover slows down the flow of water onto the earth, so it is absorbed more easily and less soil is washed away. Creatures that eat figs (a whopping 1270 kinds of birds and animals enjoy the fruits of the Ficus genus – way more than any other fruit) not only stock up on vital energy, but the little parcels they drop later when they have crawled or flown far away, increase the organic matter in arid soil, to the benefit of other animals and plants (and maybe even nourishing a baby fig tree sprouting there soon afterwards).

South of France and North of Tunisia: parallel universes

My reportage took me to rural Tunisia, down miles of potholed lanes to remote villages that hugged the edges of limestone plateaux, a few hours’ drive south of Tunis. If I thought I’d left the South of France for warmer climes, I was wrong. It was springtime, and snow on the summit of the Djebel Gorraa mountain had only recently melted, fresh water flowing down through steep gorges just as it does above the French Riviera. In fact, the view from the fig grower’s house there, in the hamlet of Djebba where I stayed (neither hotels nor Air BnB being present in the area), was extraordinarily similar to the view from my home in Vence, up to the limestone foothills of the Maritime Alps.

Yet, instead of swimming pools and villas, the lower slopes of Djebel Gorraa were carpeted green with fig and other fruit trees, vegetables and herbs – every inch used for growing food. Fig production in Tunisia was never widely industrialised, mostly still following the ancient Mediterranean tradition of small-scale, family farming. Here, no noise from machinery could be heard; donkeys ploughed the soil in among the trees; spring water trickled through an intricate network of tiny channels (to make it accessible to every family); and the dozens of tiny plots on the hillside were alive with people tending to their ‘gardens’. Such a sustainable system of polyculture, where the term ‘organic’ is irrelevant, is but a nostalgic dream in the rural West today.

Global warming shows no preference for its victims, though. Just as the idea of a swimming pool water ban is mooted in Nice, threatening fun on some people’s holidays, less and less water gushes out of the springs in Djebba, threatening supplies of food on everyone’s tables. The hot, dry hands of the desert are creeping north, and solutions need to be found, in North Africa, just as in France.

Thirsty fig trees and juicy sun prints

The potential that some fig varieties may offer Mediterranean farmers whose crops are failing in the face of global warming, and FIGGEN’s research project, had received little prior media attention. So the magazine editor and I set out to do the subject justice, with an in-depth photography-and-words reportage – and not only that. I intended to later build on the assignment with personal work, and made a series of portraits and landscapes using an analogue camera, in addition to the digital images for the magazine (nearly all the photographs on this page were made on a Rolleiflex 2.8 F with Kodak Portra film). To add a multimedia component, a videographer was hired out of Tunis to work alongside me. Yet the most unusual element to the project was my set of anthotypes prints.

In Tunisia, chosen as the case study country, varieties of the Common Fig vary greatly from place to place – the legacy of centuries of selective breeding of trees by villagers to adapt to their local climate. Cuttings of 110 varieties were gathered by FIGGEN volunteers across the country to send to a laboratory in Tunis, and variations in leaf shape and size, fruit colour and taste, were among the factors recorded for each variety before stress testing began. Yet the diversity of fig trees has dropped over recent decades. New refrigeration techniques, fast roads and faster vehicles to ride them, have brought fig sellers close at last to big, urban markets – and it seems city-dwellers favour the biggest, fattest and juiciest kinds of fig. Farmers began planting just one or two of these water-hungry varieties at the expense of many others… and no-one thought about climate change.

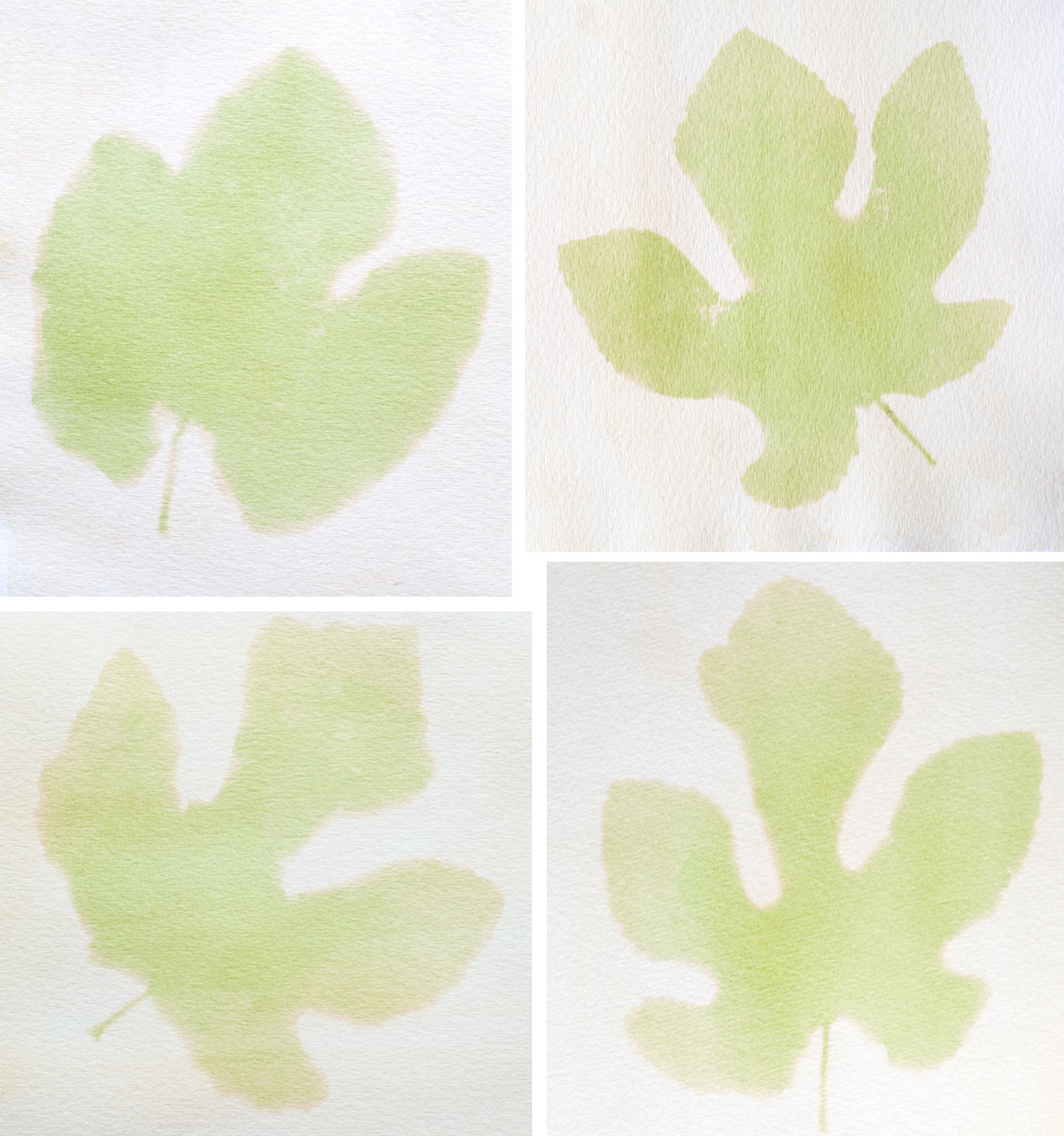

Today, this strategy is starting to backfire, and there is new curiosity about other, less thirsty varieties of fig. I collected, labelled and pressed a bunch of leaves from many different kinds of fig tree in Tunisia and, on my return to France, made from them a set of anothotypes – an alternative photographic process to make prints using plant juices and sunlight. The juice I used was of course fig leaf juice and the final prints offer a different way of considering this myriad of varieties – one particularly haunting print being made from the leaf of the last tree of its kind in a village I visited. From a set of un-thought-out selfie clips that I captured on my precariously balanced phone and unscripted chatting through single takes (never put a photographer on camera) as I worked, Aramco World’s team pulled off no small miracle to make a video of how this was done.

Four of the anthotypes I made : clockwise from top left: unrecorded, the last of its kind in the village; Hamri; Hadri; unknown variety brought from Medenine (all collected in Kesra, Tunisia)

Portraits of fig keepers

The story may have been about trees, but it was the humans I encountered who stick most in my mind, those whose lives were interwoven with the figs’ destiny. I met Amel, above, hitchhiking to her small field, far outside a village. Her husband had started growing figs there, he’d said it would be the only safe crop for his children’s future. Yet the land was poor, with no water source. He had been digging where he thought there had once been a spring, when a rock fell on him and he died.

In another district, eager, young, sports teacher Anwer showed me the result of his leisure-time research: a plan to make a low-cost watering solution to save his father’s figs trees, based on ancient Roman designs. His technical drawings illustrated the placement of giant clay urns buried underground, from which water would seep out over several days, using far less water than modern watering systems (which train roots to stay near the surface, fragilising them in times of drought).

I met Ahmed, below, on the terrace of a roadside café. It was his 89th birthday. He was proud to claim that he can identify 32 varieties of fig, and that every couple of days, he shuffles down to his garden, on the steep, terraced slopes below the village. There, he tends to his own few trees. “If I’m still in good health, it is thanks to years and years of work with my figs.”

Zina: sitting in her family’s fig garden makes her feel close to her dad, who looked after the trees before his death

Bougataya : “When I was a child, water ran everywhere here. We rarely needed to water our figs at all, there was always plenty of rain and even snow in winter. All that has changed.”

Pioneers in fig genotype research

Back at Tunis El Manar University’s Faculty of Science, the work with figs was of a rather different nature. In a university garden, the hundreds of cuttings that had been collected across Tunisia the year before, were lined up and labelled by number, enthusiastically outgrowing their pots. The day I visited, FIGGEN researchers were extracting DNA from the leaves of these plants. The process was convoluted, involving painstaking removal of leaf veins by hand; crushing the remains; adding liquid nitrogen to break down cell membranes (good to photograph – Harry Potter-style smoke); filtering them with a centrifuge; and finally, checking the purity of DNA samples obtained, with a dedicated machine and UV light. As I was both capturing images of the process as photographer and making notes on the ‘whats’ and ‘whys’ as writer, I was glad the process was repeated several times.

This was the last stage of the project in Tunisia, as stress testing of the plants had already been carried out. ‘Stress’ was the scientists’ term not mine, and it certainly sounded apt, from the point of view of the baby fig trees. First, they’d been watered progressively less and less each day, and detailed measurements had been taken of how well or not the different varieties coped (the temperature of leaves goes up and chlorophyll levels go down when a plant is ‘stressed’). Then, the same plants had been given increasingly salty water – saline soil being another characteristic of drought. Now that the varieties had been ranked according to their resilience, the DNA of test plants from all project countries (Tunisia, Turkey and Spain) was to be sent to the University of Pisa, where an eager Italian team would conduct the most comprehensive genotype study of figs ever known. Using a new technique of molecular markers, the researchers hoped be able to identify, for the first time, the exact genome sequences that make fig trees resilient to drought.

Extracting DNA from sample 28 (the ‘Romani’ fig variety) at The Tunis El Manar University Faculty of Science

Green shoots of hope

A year after my return to France, FIGGEN has accomplished its mission. The genotype results are expected to be published in scientific journals this summer. Meanwhile, the shortlist of fig varieties that performed best in drought conditions has been shared with dozens of farmers, nurseries and plant breeders in each project country – and it is no surprise that the top performers are not those which are the most widely cultivated today. It is up to people working the land, now, to choose what they will plant; it is up to breeders whether or not to use this data when creating new hybrids. But what is certain is that fig trees could contribute to the greening of lands that may otherwise be lost to cultivation entirely, as the climate gets hotter and drier – perhaps offering a green shoot of hope for dispirited farmers all around the Mediterranean. As Anwer, the teacher I met, put it:

“We must think intelligently and optimistically to find solutions – because solutions already exist to everything. There is no problem without a solution…even climate change”

Read the magazine article online or see the 12-page print layout.

> See Reportage portfolio