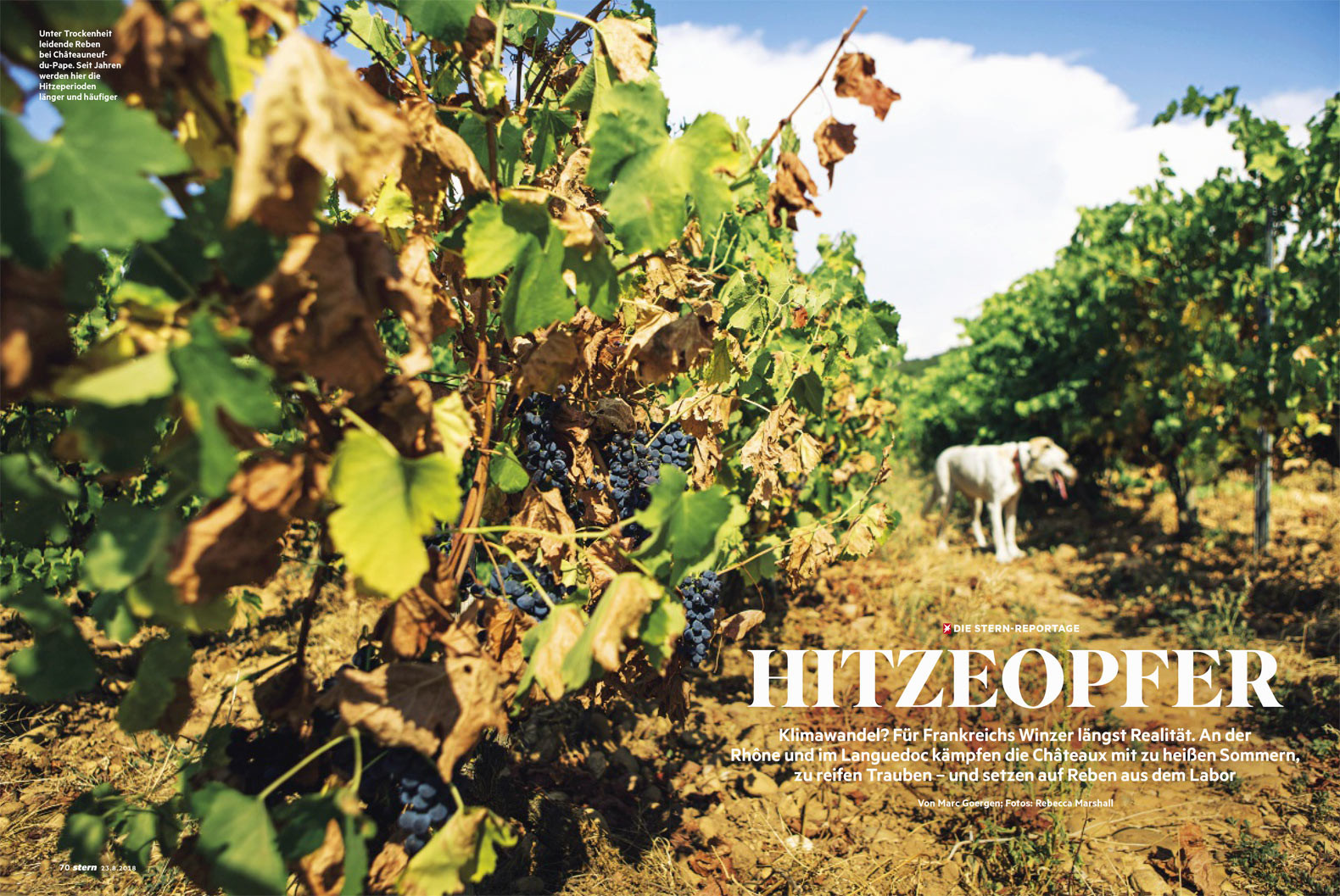

Wine and France. The two just go together. Le vin is of ultimate importance to the French economy, its way of life, history, gastronomy and, quite simply, to a sense of Frenchness. Yet the very nature of many established wines is under threat today. Global warming, and the slow increase in the temperature of the planet, is starting to make its presence felt in France’s vineyards. The impact on winemakers could shake the French wine industry to its core. This summer, Stern magazine, sent me as photographer, and journalist Marc, to the Languedoc and Rhône, two of France’s biggest – & hottest – wine-growing regions, to investigate.

Stern: “Heat Victims”. At that moment, the vines, dog and photographer were all in the same category.

When is a merlot not a merlot?

To put the problem simply, the hotter and drier the weather, the sweeter grapes become as they ripen. Sugary grapes make for wine with higher levels of alcohol. As wine changes in strength, so does the balance of acidity & tannins, and its taste. A wine made from Merlot grapes that were sweeter than usual when harvested, no longer tastes like a Merlot. Therefore it can be argued that it no longer is a Merlot (or is it? a question worthy of Descartes, perhaps). With a €13 billion wine export industry at stake, the problem is more than philosophical.

Our first interviewee for the article was no new kid on the block. Laurent Charvin is an 8th generation wine-maker at La Domaine Charvin, situated close to the village of Châteauneuf-du-Pape. With a family knowledge of local weather and its influence on grapes dating back to the 1850s, Laurent concedes that the climate is indeed apparently changing. “It has always been hot during South of France summers, but long periods where the temperature remains at over 30º are occurring more often today. 50 years ago, my grandad would harvest our grapes at the end of September – but they are ripening earlier and earlier. To catch the grapes at the same stage in the cycle, we’ll be harvesting at the end of August this year”

Ancient vines and new ideas

The timing of our assignment turned out to be very appropriate to the feature, and also very uncomfortable for a photographer working outdoors. It was la canicule, a heatwave, and the temperature in the shade (if you could find any in open wine country) was 38º plus. Marc, the writer, looked relieved to conduct Laurent’s interview in his cool cave [wine cellar], and I found myself particularly interested to listen in. The time I spent photographing the vines and farm, sizzling under the midday sun, was minimal.

Laurent’s domaine is organic and, in his wine-making, he practises refreshingly low-tech solutions to hot climate problems. He spoke affectionately of his vines (a mix of Grenache and Syrah varieties); he has known them a long time. Most are over 50 and some of his vines are still producing grapes for him at 100 years old – which is rare in France. When Laurent’s vines at last reach the end of life, he removes them and lets the soil rest for no less than 7 years before re-planting. He has a particular technique for planting new vines to promote strong downward root growth so that they can always find water, however hot it gets. Indeed, he believes watering vines is very bad practise as it limits their capacity to adapt to a drier climate. Unlike other vignerons, he doesn’t cut the leaves of his vines back either: the extra shade reduces evaporation. During the actual wine-making process, he has recently taken to throwing green vine leaf shoots in with the grapes during fermentation, to add freshness and help keep the percentage of alcohol in the wine lower.

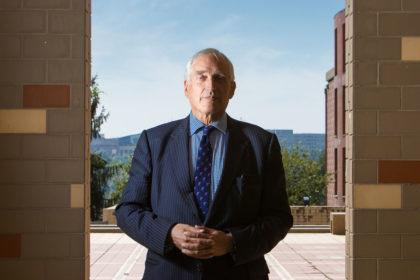

Interesting conversation and the subsequent tasting (and re-tasting) of a couple of Laurent’s particularly fine Châteauneuf-du-Pape cuvées had made me almost forget that I was there as a photographer. When it was time to make Laurent’s portrait, I decided that for everyone’s comfort (Marc helped me, a perfect photographer’s assistant), we would avoid the furnace-like conditions outdoors and do the first set-up at least in la cave. Laurent’s smile was slightly more genial than that I generally look for in an editorial portrait, but I was feeling too genial by then to intervene.

Scientists, clones and southern imposters

Further south, slap bang on the Mediterranean coast, lies the French Wine and Vine Institute. This organisation, the nerve centre of France’s wine industry, is quietly taking a much more scientific approach to managing the impending climate change crisis (no-one, of course, referred to it as that in our hearing). Here, 40 hectares of coastal land have served for decades as both national storage for France’s 500 + grape varieties, and as a centre for disease-free reproduction, cultivation and certification of vines. No less than 95% of the vines in France originate from this site south of Montpellier, and scientists here have long been working on improvements in vine growth and wine-making. However, the last 15 years have seen a new agenda becoming increasingly important: working out how French wine can cope with a hotter climate. The relevance of their work must be keenly felt by researchers right now: the whole site is currently moving to a new location, as rising sea levels are starting to interfere with their vineyards and office building.

Wine-makers in areas slightly further north, such as the Côtes du Rhône, used to have to add sugar to the grapes during fermentation to bring wine to maturation. That is rarely required anymore, explained the centre manager, Pascal. Over in Bordeaux, vignerons are now planting grape varieties originating from the South of France as things heat up. “Even England is starting to make decent wine“, he quipped. When it comes to wine-making in the South of France, the experts are looking even further south. Grape varieties native to other, warmer countries like Portugal and Italy are being tested. Sacré bleu! Pascal skirted around this topic, one that I suspect is highly controversial among French vignerons, oenophiles and casual nationalists alike.

Other techniques being tested include the development of entirely new grape varieties. Every pip in each grape contains an entirely different genetic profile, and current pollenisation attempts include even wild vine strains from the USA and Asia to create grapes that cope better with the heat. The idea is that these can then be mixed with existing grapes to preserve a known wine. Merlot grapes, for example, are particularly prone to higher levels of sugar, making wines of up to an unacceptable 15º. One new variety of grape developed here however, the Artaban, never exceeds 11º in fermentation, however warm the weather – so cunningly mixing in some Artaban with a Merlot can enable a hot-summer Merlot to remain nonetheless a Merlot. Up to 15% of a Merlot wine can legitimately be made from another grape without it being stated on the bottle.

We toured greenhouses, experimental vineyards, nurseries and laboratories. Tastings of wine from various experimental new grape varieties took the edge off some of the more complicated scientific explanations.

Best-stocked wine cellar in the south

You could buy a car, a holiday to the Maldives and a designer outfit – or drink this bottle of wine with dinner

Back at the consumer end of things, the Oustau de Baumanière restaurant in les Baux-de-Provence boasts the biggest wine cellar in the South of France. The cave under the hushed dining room contains no fewer than 25 000 bottles. As many bottles again are kept in a nearby, not-to-be-named, village, in a cave that was hewn out of a cliff centuries ago, and is now protected by an unmarked door (and fingerprint security access).

The restaurant may have 2 Michelin stars, with starters on the menu priced at upwards of 60€, but I got the distinct feeling that the food represents more of an accompaniment to the wine than the main event here. Our host, in any case, did nothing to dispel this impression. Gilles Ozzello, sommelier-in-chief (of a team of 5), has been working with wine here for 40 years and appeared to know every inch of the caves by heart. During our tour, I asked to photograph a bottle that I spied in a fridge with a particularly old-looking label. As I was turning it to the light, Marc spotted the wine on the carte des vins. A blank nothing represented its price. How much would someone need to part with to order this 1870 vintage Chateau Lafite-Rothschild with dinner, he asked? Fortunately, it was only my jaw that dropped on hearing Mr Ozzello’s response: €25,000. I’m not sure that my photographer’s insurance would’ve covered the damage if, in my sudden surprise, I had let the bottle slip from my hand.

On the subject of global warming and its impact on French wine, Gilles remained distinctly quiet. Do his clients know or care about it? I suspect that if they’re drinking up vintages of over 100 years old, then any changes won’t be felt until long after his time as a sommelier here.