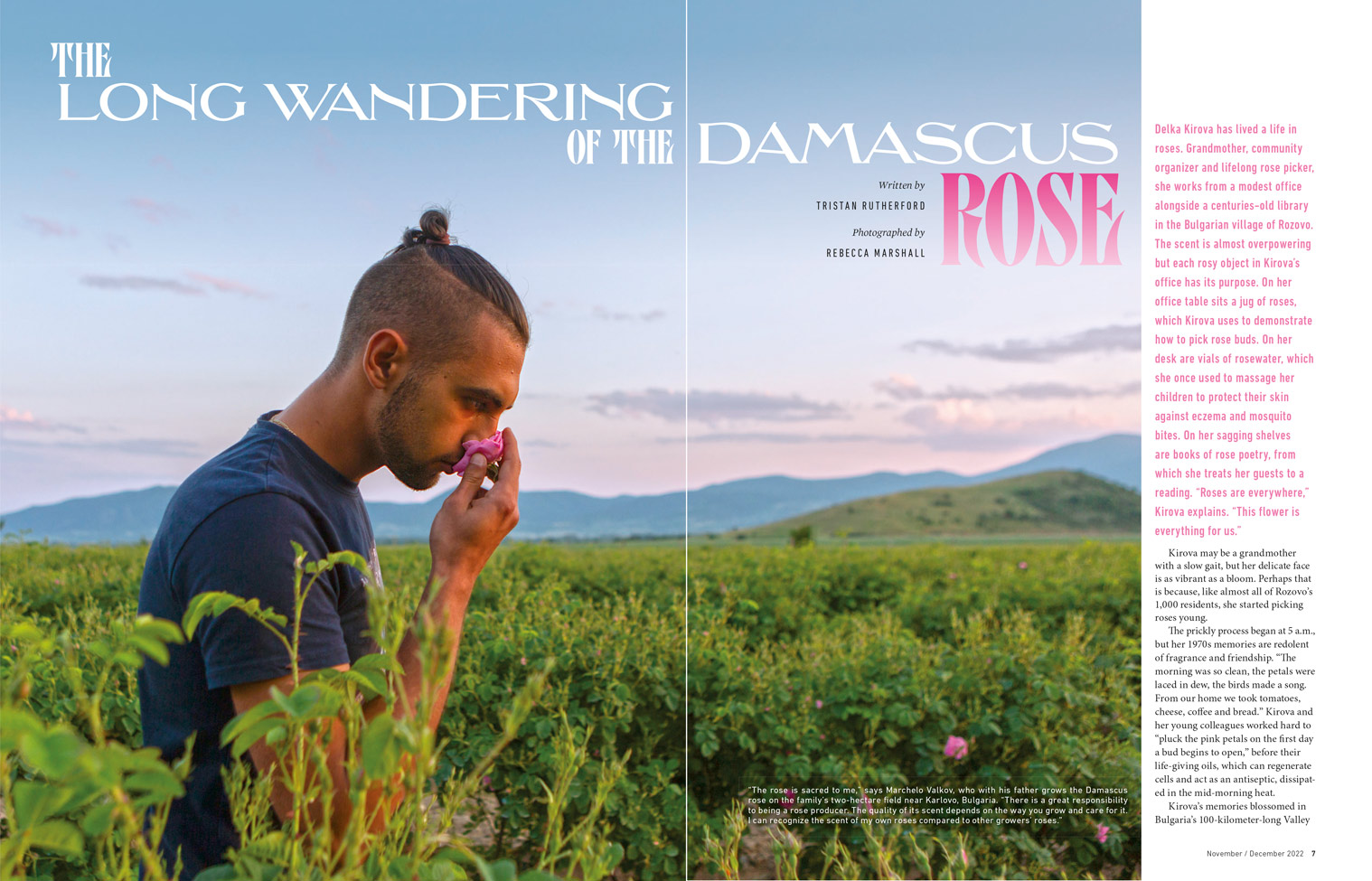

“The [Damascus] rose is sacred to me. Its power and scent quality depend on the way you grow and care for it. I can recognise the scent of my own roses compared to other growers’ roses”

Rose oil producer Marchelo Valov’s words lacked neither pride nor passion, as he assessed his rose blooms near Karlovo, Bulgaria. I’d been sent to the Valley of Roses as photographer for Aramco World magazine (other collaborations include Egypt’s electronic music scene & Morocco’s cinema industry) and this assignment should have been straightforward; yet it was anything but. I took the photograph above just hours before I flew home – achieving it wasn’t far short of a miracle.

Late bloomers

Bulgaria can indeed boast about its roses: the country produces the highest quality rose oil in the world. Close to Bulgaria’s centre lies the Valley of Roses, a 100 km-long, flat basin where the majority of the country’s finest blooms are grown. The picking season is short, lasting only around 20 days. With prior experience of lavender and saffron harvests, I knew it was wise to heed the local producers’ advice. Writer Tristan and I should plan our trip for mid-May, they told us, when harvesting and distilling of the rose oil would be in full spate. Yet, on arrival, we were met with decidedly sheepish looks: “The climate is kind of weird this year…everything is a bit late...”

Queen of roses

There are more than 7,000 different species of rose, yet the Damascus variety, Rosa damascena, produces oil with the most complex, long-lasting, rose scent known to perfumers. Originally from the Uzbekistan-Afghanistan region, this rose’s petals were distilled in a crude form as far back as 4000 BC. Brought to Bulgaria from Syria in the 17th century, it flourished instantly in its new home. Winters in the Valley of Roses are relatively warm, and the temperature rises slowly and gradually in spring, thanks to cool breezes flowing down from the Balkan mountains – allowing the roses extra time to grow high quality, oil-filled blossoms. The deep, sandy soil drains well, which, with high rainfall and plentiful groundwater, makes for a rose heaven – and a blossoming rose oil industry. Apart from the scent (see my reportage on the perfume business) and culinary uses of roses, the medical merits claimed by Damascus rose oil are impressive: from antiseptic properties and easing menstrual cramps, to regenerating skin after burns and slowing the rate of ageing.

Rose queen of photographers

Yet the fine rose bushes I could see, stretching from the train window to the distant horizon on the last few miles of our ride from Sofia to Kazanlak (the capital of Valley of Roses) were markedly flowerless. Tristan began his interview schedule regardless, and I made portraits of the subjects.

In the village of Rozovo [“Pink“], we met grandmother and lifelong rose picker, Delka. I made a portrait of her holding a rose plucked from a bush in the churchyard… but it wasn’t a Damascus rose. I photographed a beautiful representative of the Alteya distillery, which exports its organic rose oil products to 75 countries, in the middle of the farm’s rose fields… but instead of blooms, she was framed by buds. At the Kazanlak Rose Museum, I had the honour of sniffing the divine scent lingering in an alambik, a copper distilling cauldron that had been used for making Damascus rose oil, but -incredibly- it hadn’t had a rose in it since 1947. For 4 days I went out to the fields, hoping to see rosebuds opening, but in vain, and even my delight at dining in restaurants with items like ‘bunny in the potty’ and ‘pork in the oven’ on the menu was slightly dimmed. The mayor of Kazanlak, perhaps as consolation, lent me the valley’s Rose Queen crown to try on in her office, the day before a giant, annual Rose Festival pageant was held in Kazanlak’s packed auditorium, so I even had my own beauty queen moment, before the crown was placed on a more deserving, well-groomed head.

All this didn’t change the fact I hadn’t photographed a single Damascus rose, and Tristan’s unruffled optimism (“Don’t worry, they’ll come out in a day or two“) was that of a writer who has more leeway than a photographer in such a situation. I had only a week in Bulgaria, with just 2 days left. Photos of flowers would be essential to a 10-page magazine article about roses and, though a helpful friend suggested it, scrunched up pink crepe paper stuck on bushes wouldn’t cut it.

Unlikely saviour

Once Tristan had left, I decided to head 50 km west to the little town of Karlovo. Still in the Valley of Roses, yet at a slightly lower altitude than Kazanlak, I reasoned that it might be a bit warmer – and an earlier blooming. However, with such little time, no contacts there and no translator, it wasn’t going to be easy, and my heart sank on arrival, when I saw the train station’s little rose bushes still in bud. But anyone who knows me well, knows that I don’t give up easily. The owner of my guest house understood, from my expansive and slightly desperate gestures, the need for a vehicle to find flowers, and he presented his son Dmitri for the task. A college student of 18, Dmitri appeared delighted to be at the wheel of his dad’s car, speeding around with a photographer on a mission – and he turned out to be my unlikely saviour.

As we sped onto the open road, I couldn’t believe my eyes: there were odd spots of pink in the rose fields! We stopped so that I could photograph them – but I was still missing the critical rose harvest itself. Dimitri called the rose-growing father of a friend, but “No, they haven’t begun the picking yet“. Seeing my face, he tried another. And another. But it seemed that no-one in the Valley of Roses had enough blooms to start harvesting yet. Then, thanks in greater part to his adolescent male pride than my own private prayers, he gave it one last try, calling a friend of a friend: a small producer. It was possible that he might consider beginning the picking of the few blooms he had… tomorrow!

Dumbstruck by scent

We burned back into town, killed time in a bar on Dmitri’s estate (giving him a nice chance to publicly toss around the keys of his Dad’s car) and eventually drove to the ‘drop’. A few suspenseful minutes later, the back door opened, Marchelo Valkov slid in and leaned forward, his hands cupped. “Pleased to meet you, Rebecca“. He opened his hands, and there was one of his roses. According to official perfumer speak, the 300 essential oil components of Bulgarian roses from Kazanlak give the flowers a “warm, colourful, extra dense scent with a slightly pungent honey flavour“. At that point I didn’t care about words, momentarily dumbstruck by the exquisite scent.

Rose picking begins at dawn and is over by mid-morning, when the heat of the sun would cause essential oils to evaporate. All my fingers were crossed as we bounced down the valley, along miles of rough tracks, to reach Marchelo’s 2 hectares and assess whether there were enough rose blooms to warrant a small, first harvest the next morning. We arrived at his perfect, photogenic rose fields just as the sun reached the horizon, and, as I took sunset portraits of Marchelo, the photographer in me was happy at last. In the gathering dark, it was decided that the next morning’s rose picking was on. I would see what would probably be the first harvest of the year in the Valley of Roses.

Coming up smelling of roses

Still, at 5 am the next day, as I stood shivering in the field, hope almost deserted me again. Dmitri’s dad (who’d driven me there, Dmitri apparently exhausted by the previous day’s efforts) pointed out the brightening sky, and said it was too late, they couldn’t be coming. Yet I stood, rooted to the spot. Thankfully, minutes later, we saw a flume of dust on the horizon: the pickers were here!

No machine exists to automate the delicate plucking of rose flowers. Only three pickers came that morning (the few blooms didn’t justify more) and no-one was in the first flush of youth – the eldest, Christoph, was 80. Rose pickers earn very little -1 lev (0.50€) per kilo of roses picked-, and that day, no-one was likely to clock up more than 10-15 kg. So generally it is only migrant workers, the unemployed and grannies and grandads who show up for the work. It takes around 3,000 kilos of Damascus roses to make 1 kg of rose oil: an eye-watering amount of labour for the end result.

By the time the sun was high in the sky and the pickers had weighed their sacks, my time was up – it would be tight to make my train and reach Sofia for my afternoon flight. As I boarded the plane to Nice, memory cards full of rose images now safely backed up, and mud from the Valley of Roses on my jeans, I breathed a considerable sigh of relief. 6 months on, my jeans may be cleaner, but the rose Marchelo gave me, squashed in the back pocket of my diary, still smells incredible…

> See Reportage portfolio