The Karabakh is one of the oldest breeds of horse in the world. Hailing from the mountainous Karabakh region of Azerbaijan, these horses are known for their stunning golden coats, endurance and speed. Yet Karabakhs nearly became extinct in recent times, with only around 50 purebred horses left in the 1990s. Since then, considerable efforts have been made to safeguard the future of Azerbaijan’s beloved national animal. I travelled there as photographer to shoot this cover story.

Polo diplomacy

According to writer Tristan, this would be the first international magazine feature on the subject. Prior to the trip, I had photographer dreams of capturing a herd of golden horses, sweeping majestically across a beautiful mountainside… making portraits of a hardy herdsman, legs moulded around his trusty Karabakh steed… Yet the assignment turned out not to be like that at all. In fact, over half my week in the country had passed before I even saw a Karabakh horse.

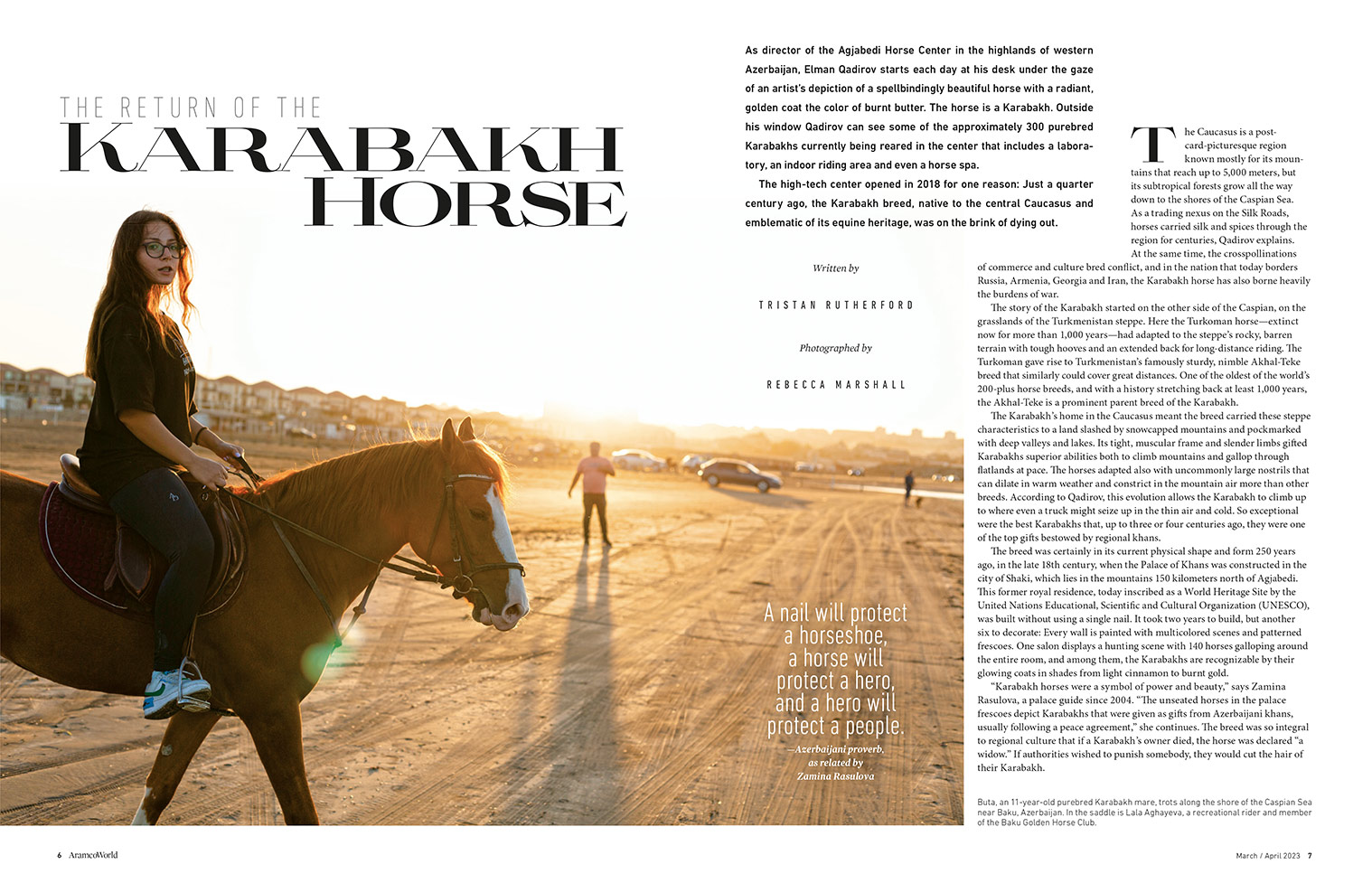

Upon arrival in Baku, our first meeting was with a diplomat. In a country where media visits are keenly ‘facilitated’, even a national horse breeding programme must be covered ‘properly’, and Tristan, who’d smoothed our way at the embassy, was advised in no uncertain terms as to who to interview – and who not to. He cordially assented, and so we were invited to a polo match at the Equestrian Federation of Azerbaijan, packaged with a meeting with the Federation’s Secretary General, seated at his giant, polished desk, under a giant, gold-framed portrait of the country’s president.

The polo match was certainly entertaining. Seated at the edge of the field, we were among a handful of honoured guests (fine nibbles were served by attentive waiters) and the commentator, who worked from a spot next to our sofa, introduced himself to me as “the voice of international polo” and took it upon himself to give a TV shout out to “special guest Rebecca!“. At the break, he presented us to a General who, installed two tables down behind a screen of watchful helpers, was allegedly the Azerbaijani president’s right hand man, mastermind of Azerbaijan’s role in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. The General emitted some cordial pleasantries about the country’s national horse, but his smiles seemed mostly due to the day’s final draw between the USA polo team and the Azeri home team (a result which I hadn’t predicted at all, given the dazzling, superior play of the Americans in the first 30 minutes). However, my own goals as an assignment photographer had not been furthered: the polo ponies were not Karabakhs but Thoroughbreds.

Bears and berries – but no Karabakhs

Our next stop was Sheki, a little town 5 hours northwest of Baku, nestled at the foot of the Caucasus mountains. Once upon a time, Sheki was an important Silk Road trading post, and in the early 1900s, it was a gathering point, where selections of Karabakh horses were made before taking them to sell in Europe, or nearby Russia – a short ride over the mountain peaks above.

Tristan was delighted to record the director of the 18th century Palace of Khans (Sheki’s only tourist attraction and on the ‘Interview: Yes’ list) waxing lyrical about the historical importance of Karabakh horses. Yet apart from horsey frescoes on the wall of a palace salon, and a statue rearing up over the city’s gate, there was little there for the committed assignment photographer. I spent a long weekend hiking (an activity highly discouraged by locals, due to the presence of hungry bears in the mountains – I did come back down from my solo hike when I nearly stepped in the largest poop I had ever seen); trekking to an off-the-map, natural hammam (in a tiny shack built out of a repurposed Soviet train carriage, halfway up a cliff, over a geyser pumping steaming water out of the rock); eating blackberries; and riding up the mountain behind Sheki on a village horse (not Karabakh) to see the wild Russian border (an exploit that took 9 hours and caused me to walk like a cowboy for days). But still I saw no Karabakhs, and was starting to get anxious. I had a 10-page feature about them to photograph, and time was ticking by.

From the brink of extinction to a safe haven

A photographer visiting rural Azerbaijan 150 years ago would have pictures a’plenty of golden horses in the bag by this point. Yet Karabakh horses all but died out during the following century. Russians took many away for use as pack horses during the country’s Soviet Union rule; others were sold abroad to generate precious US $; many were killed in action or from food shortages during various conflicts in the Caucasus. The handful that remained in their native war-torn Nagorno-Karabakh region, were saved from shelling and other perils in 1993 by a group of dedicated stablehands. In a sort of ‘Moses and the Exodus’ manoeuvre, they were led east to the safer plains of Agjabedi – where a national Karabakh horse centre was subsequently established. Sales of Karabakhs abroad were banned, and a controlled, pure-blood breeding programme was launched. Fast forward to today: Karabakhs seem only to be present in registered, pedigree form (according to our diplomat-recommended interviewees). The breeding programme has been successful in boosting their numbers, and the ban on overseas sales has been lifted recently. Yet each horse (with its DNA record, multi-generation proven parentage and passport) is gold in terms of value as well as colour: a fine specimen can be sold for up to 25 000 €. So, to see Karabakhs, we travelled to the Agjabedi Horse Centre, where a number of these specimens live rather sheltered, privileged lives.

Treadmills for golden horses

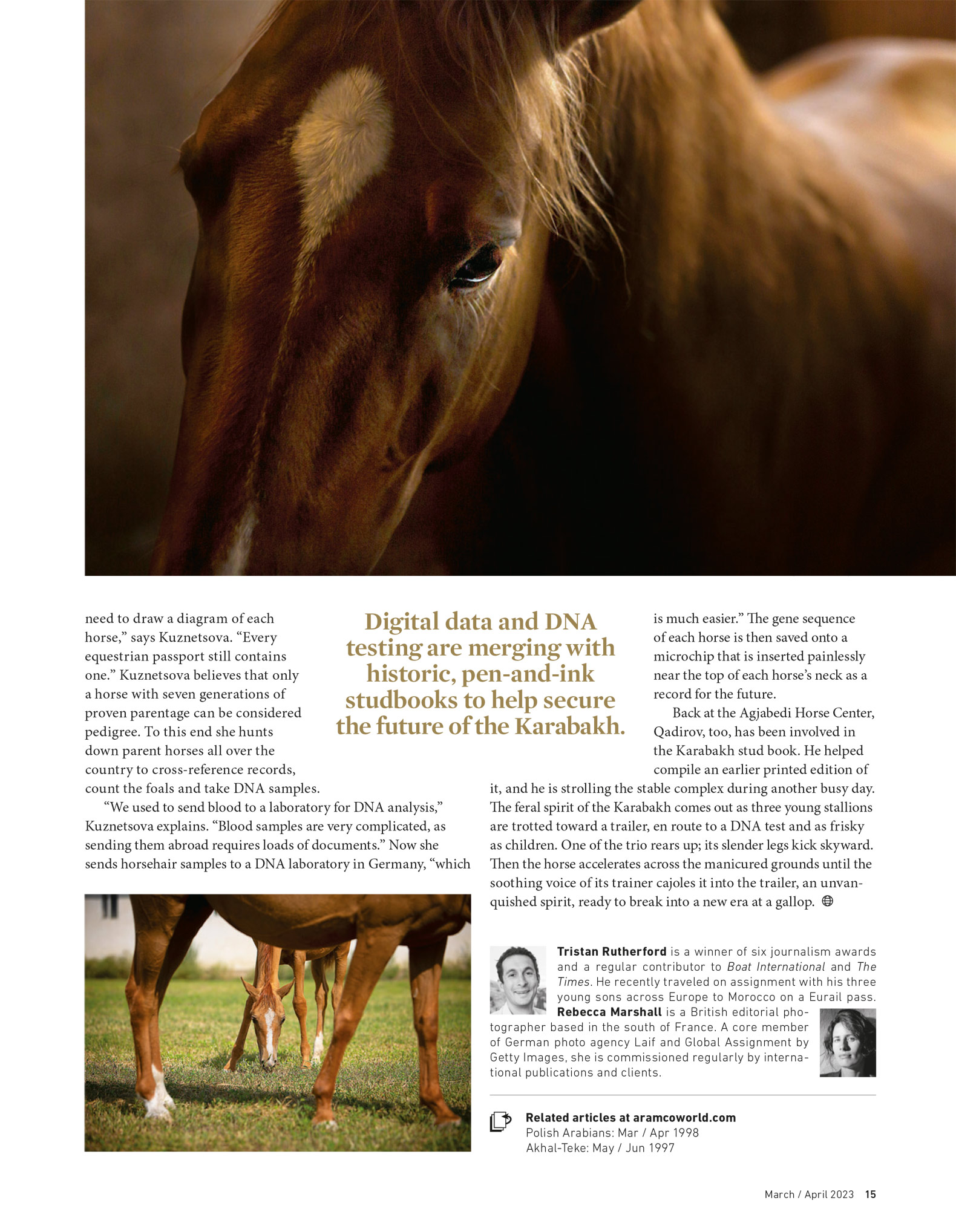

Individual serviced quarters, exercise machines, massage – the accommodation and spa facilities to which these horses are accustomed, would be the envy of many two-legged creatures…and they clearly thrive on it. The best examples to show a photographer were deemed to be the young stallions, and the colour, grace and beauty of the first Karabakh horses I had ever seen, took my breath away. I’m no stranger to horses (the meaning of my surname Marshall is ‘horse servant’, my great-grandfather was a horse breeder, and I spent much of my childhood on, or wanting to be on, a pony) so it was a particular delight for me to get up close to these Karabakh stallions.

A medium-sized horse, the Karabakh is extremely well adapted to life in its native mountain home. Their skin is fine yet tough; their hooves are small, good for picking a way up rocky ascents; their nostrils large to facilitate breathing at altitude. The coat of a Karabakh horse does not have to be a golden-bay colour, but all these prime stallions at stud were positively glowing gold, even inside their stables. “These horses haven’t ever seen the Karabakh region” said Elman, director of the Agjabedi Horse Centre, “but the day they go, eat the grasses and drink the mountain spring water there, the colour of their coats will become an even brighter, vivid gold“.

Charged by a half tonne of crazy horse

My experience with horses was useful when photographing the stallions up close. The Karabakhs seemed friendly, but any stallion commands respect, especially in its confined territory, and the one whose stall it was suggested I enter (presumably because he wasn’t prone to kicking or biting) vacillated between intensely curious – and intensely impatient. Even Elman had the devil of a job posing for a still portrait with the stud’s star stallion, and I detected beads of nervous sweat on his brow, as he grappled with the conflict of interest between showing off his best horse to the photographer, and having that lively beast on the end of a short rope beside him.

It wasn’t until I was outside, though, that I ticked off one of my 9 lives. These stallions have two main occupations in life: racing (at an impressive top speed of 52 km/hr), and inseminating females. That day, 4 lucky beasts were to be loaned out to perform the latter activity, and I photographed them being led from the stables to their horsebox. Perhaps it was because they don’t get out of their stalls or the indoor arena that often, or perhaps it was the anticipation of their exciting mission…but they were lively, each stallion a handful for their handler. As they skirted the giant lawn, one broke free, and set off at a breakneck gallop around the topiaries. Faithful to my photographer instincts, I lined his distant frame up in my sights, and snapped a single frame…before realising that he had abruptly changed course, and was heading straight towards me. My lens showed the whites of his eyes and I let the camera drop. I stood still, thinking “he won’t surely gallop straight into me“…. until the very last second, when I realised, he actually would. A giant step to the side as he thundered past narrowly avoided a catastrophic end to my Azerbaijan assignment.

Back to Baku

After our visit to Agjabedi, Tristan announced that he was done, and I waved him off on a bus in the direction of neighbouring Georgia. However, it was not yet holiday time for me. A photographer can’t catch up any missing details by phone later…and after one day at a horse farm, I clearly didn’t have an adequate range of images for this extensive feature. No longer with a set schedule, or the luxury of an interpreter, I decided to travel back to Baku, where I had a couple of leads.

Firstly, I unearthed a flame-haired horsewoman called Svetlana, who was none other than the Karabakh DNA registrar. I made her portrait at a stable that hadn’t been on the diplomatically-approved location list (it was less than immaculate, and some of the horses -not all Karabakhs- looked anorexic), and she patiently explained the system for verifying horses’ pedigrees. She visits locations all over the country to take samples of horses purporting to be Karabakh, yet the ‘national’ registration project goes well beyond Azerbaijan’s borders. DNA is sent to a lab in Germany for testing, and the breeding programme is supported by American funding.

However, it was on the following day that I made the magazine cover photograph. I’d contacted Sarxan Tagiyev, founder of the Baku Golden Horse equestrian club and ex-champion jockey, whose grandfather had begun collecting Karabakh horses after World War II. We met at stables beside the Baku hippodrome, under the windows of dozens of Soviet-era tower blocks. Here, 30 ‘golden horses’ lived and exercised, and a makeshift village of dwellings alongside housed the families of the devoted stablehands who’d left their homes to save the country’s last Karabakhs in 1993. Few there spoke English. My beginner’s Russian & Google Translate served me well though, and my Azeri vocabulary, coming on apace, but still fairly limited to “At” (horse), “It” (dog), “Chai” (the same word for ‘river’ and ‘tea’) and “Shimshai” (lightening), filled some odd gaps in conversation.

Sunset cover

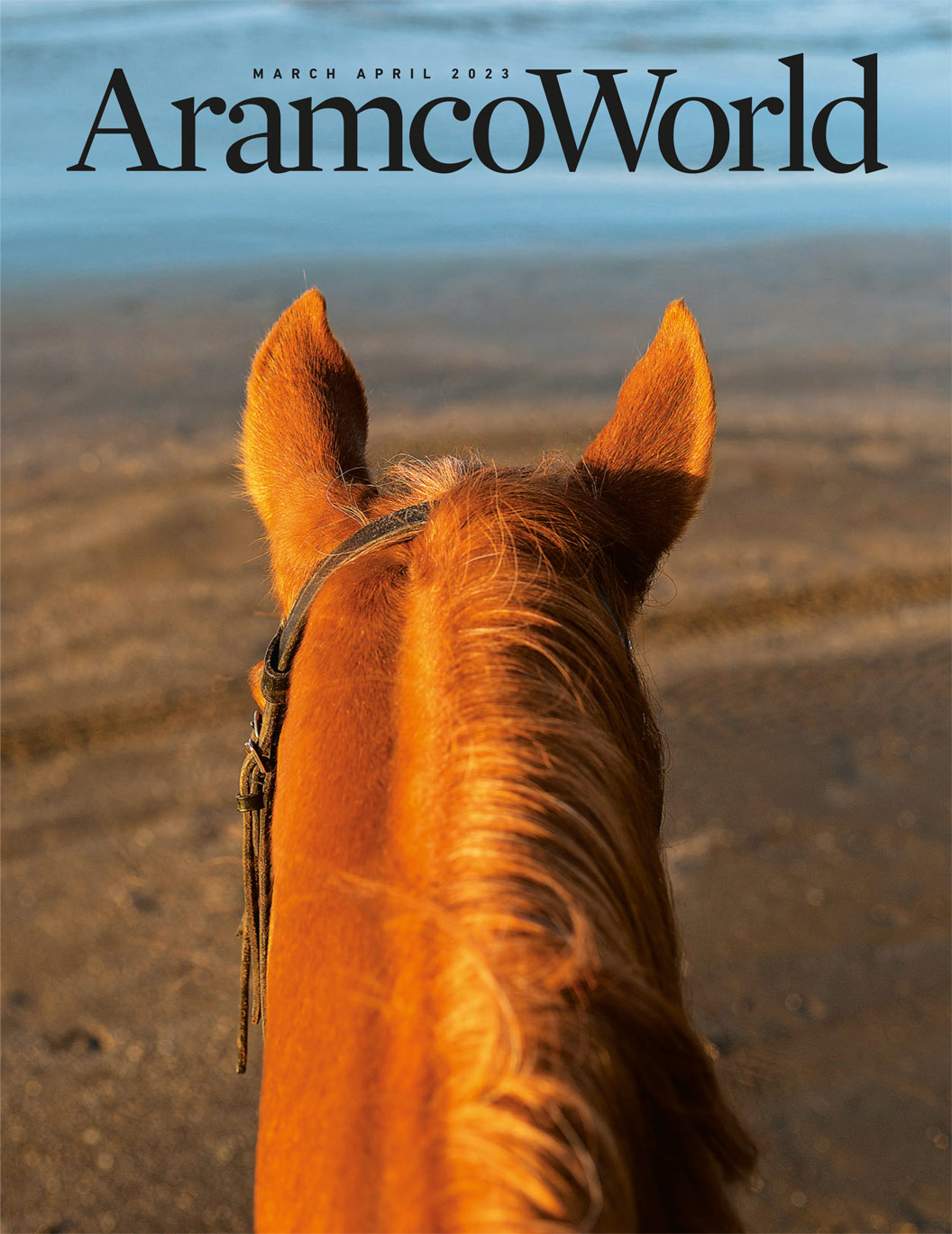

Despite communication challenges, Sarxan was a marvellous host and subject, quickly understanding exactly what a photographer might need. At his suggestion, after I’d made his portrait and taken some reportage images of horses training at the hippodrome, a calm Karabakh mare named Buta was bundled into a trailer and a group of us set off for… the beach.

The afternoon was coming to an end by the time we reached the shores of the Caspian Sea at Buzovna, a short drive northeast of Baku. It was the first beach I’d seen where, instead of parking on the road and walking down to the sea, beach-goers drove their cars over the sand to park by the water. The sand was, as a result, criss-crossed with tyre marks, and the air was tinged with a scent of petrol and the hum of engines – but this took nothing away from Buta’s beauty there.

The golden, near-sunset light was making her coat glow, and I took photographs of an enthusiastic, young horse club member delightedly trotting the horse up and down. All the ingredients were there, and I almost, almost had the cover. Then, in a flash of inspiration, childhood dreams merged with an idea for a photograph, and I asked to get up in the saddle myself.

Buta indulged me, stood still and gazed out toward the Caspian Sea, as I trained my camera on her golden ears. Once I knew I had the shot, I took hold of the reins, and rode up the beach. My mission as photographer accomplished, this was my moment. To ride a precious golden horse along the shoreline of the Caspian Sea at sunset: a truly golden opportunity.

Read the full article at Aramco World magazine.

> See Reportage portfolio