The call about this Saturday morning portrait shoot came at 5 pm the day before. The Guardian was planning an annual ‘Conversations‘ special for the weekend magazine, and an extra celebrity pairing had been added to the feature last-minute. Time was tight to get the photographers’ work to the designer for layout, and the fact that one subject was on holiday in the South of France was not going to scupper the plan. Could I help in a tight spot? When I said yes, I had no idea how tight the spot would turn out to be.

Photographer, assistant and stylist rolled into one

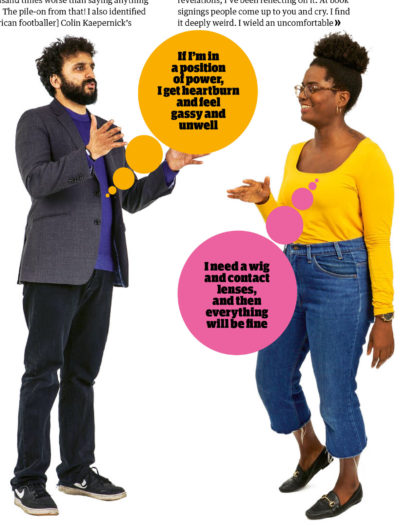

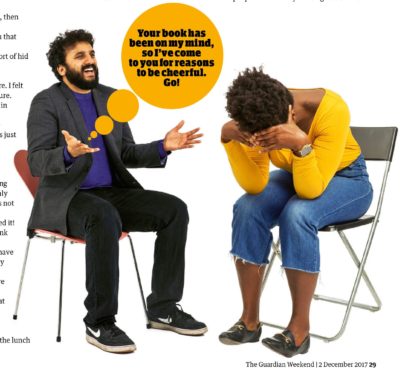

As an editorial photographer, I am no stranger to last-minute assignments…but this one did look more complicated than usual. The photoshoot wasn’t to happen in nearby Nice, Monaco or Cannes, but in Marseille – a two hour drive away from the French Riviera. The magazine’s designer would make a composite image to make it seem as though my subject, Reni Eddo-Lodge, and her conversation partner were chatting together. Reni’s portrait would therefore need to be shot and lit in exactly the same way as the other subject’s portrait, and against a white background.

Ideally, a studio would be required and the photo editor figured that I could book one. I, however, know how South of France businesses operate late Friday afternoon [they don’t – they’re closed], and figured that I couldn’t. We decided that I’d have to settle for a large room, and he agreed to find and book it (a hotel meeting room or large apartment), as Eddo-Lodge apparently didn’t want me in her holiday home.

Given that I would need to take all my own studio lighting, the next task would be to book an assistant. I called around, but, at that late stage, everyone already had plans. Ditto for a make-up artist and stylist (both had been arranged for the other shoots in the feature). My photo editor had a back-up plan, though: “Do you mind just keeping an eye on what she wears, how she does her make-up and look out for shine on her face?” I cancelled my Friday evening and started preparing.

Punch-packing feminist

Reni Eddo-Lodge is no flunky. A journalist by trade, she writes about feminism and structural racism. Her provocative book debut, “Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race“, garnered more media attention in the UK than was expected on its recent release. So after being in constant demand to talk to the press about it (and let’s not forget she didn’t want to talk to white people about race anyway), Reni had at last booked a peaceful getaway to the South of France for a few days. Or so she thought, until a long Skype interview was diarised and a portrait photographer was on the way over (yes, my photo editor had been delighted to announce, late Friday night, that Eddo-Lodge had finally agreed to doing the shoot chez elle).

What no-one had told me was that Reni’s holiday home was the size of a small shoebox.

No swinging a cat

After carrying a carful of heavy equipment up flights of stairs, I was shown the flat and realised immediately that I had a big problem. This was not a South-of-France-luxury pad; it was a tiny, student flat crammed with furniture, and I was a photographer with a specific, space-hungry brief.

A backdrop and studio lights need room, as fellow photographers will understand. For any interested non-photographer: the stands for a background paper roll don’t fit tight against a wall. Flashes lighting the white backdrop (fitted with large umbrellas) need to be placed well in front, to ensure that it is evenly-lit. The portrait subject needs to stand forward of these lights, out of range of flare. Then the main flashes, and their bulky light modifiers, are placed a little distance in front of the subject. Lastly, the photographer is positioned considerably forward of the subject to use a lens that will not distort them (a portrait shot on a wide-angle lens isn’t the most flattering). Fitting a full-length, standing person into a picture means the photographer being further away still.

I called the photo editor and dragged him away from his Saturday activities:

“There isn’t enough room to swing a cat in the largest room here, let alone take a full-length portrait on a 50 mm lens,” I said.

“But you can’t use a wide lens! It has to be 50 mm to match the others,” he said.

“Walls cannot be moved,” I said.

Ceiling’s the limit

Sensing that the call wasn’t going anywhere, and aware of the clock ticking, I cut our chat short. Reni would be joining her phone-in interview in less than an hour. The only way to achieve anything was to move kitchen appliances in the next room, take the adjoining door off its hinges, angle the backdrop in the corner of the lounge and then, once the lights were set-up, photograph Reni through the doorway, from a position wedged between fridge and kitchen cupboards. The door frame would be in all the shots, as would the light stands, umbrellas, cables and furniture piled up to the side of the backdrop, but this was the only way (and the designer intended to cut her picture out anyway).

I was briefed to work with super-soft light, and, the night before, had prepared my set-up. Reni has 2 features that a portrait photographer needs to pay attention to: firstly her dark skin needs to be exposed properly, without over-exposing any pale-coloured clothes she might wear, and secondly, lights must be positioned to avoid reflections in the glasses she wears. Given how my day was going, it was no surprise to discover that the ceiling was too low to raise the light stand and umbrella high enough for my planned configuration. I had to rapidly re-think. The one blessing of this ceiling was that it was white, so I knew it could, in a pinch, function as a large umbrella in itself. I was in a pinch.

Solidarity saves the day

Fortunately, Reni was cool. Perhaps she was driven by a sense of female solidarity, or journalist solidarity… or perhaps simple recognition of impending doom, but in the absence of an assistant she set to and helped. She was indeed so cool that she didn’t lose it when, moving furniture, we managed to unplug the wifi, critical for her upcoming conference call (we lost 15 minutes trying to fathom a sea of cables to reconnect it). She was coolly receptive, too, to my advice on make-up, controlled her own levels of post-sofa-lifting shine with a towel and was not precious about clothes changes.

Once we were ready to go, she quickly understood what was needed (which was fortunate, since we had only 5 minutes left). Reni pretended, with very little direction, that she was chatting and laughing with her invisible interlocutor, in the variety of positions, expressions and angles needed to give the designer enough choice of material to make a believable series of composite conversation pictures.

Amazeballs

After the last photo, Reni ran off to dial into the telephone interview and I sat, stunned, surveying the chaos around me. Packing up and putting furniture back could wait, I thought. It was a beautiful South of France day and I was hungry. I walked to a nearby boulangerie, tucked into a delicious ham and cheese sandwich on a café terrace and selected a couple of fine-looking macaroons to take back and slip Reni during her call.

A late night Saturday deadline meant that, after driving home, I spent the evening editing, optimising and wiring the photographs over to the Guardian. By the time the last high resolution picture had been filed, my eyelids were starting to droop. But I nonetheless messaged a few low res versions from my phone to the perhaps-still-concerned-although-probably-now-out-having-fun photo editor. His reply was quick, succinct and…somewhat unusual. Despite myself, I smiled.

“Wot amazeballs!! Great work Rebecca!”

Nadia

Jan 31, 2018 at 6:10 pm

Wow! What a remarkable story and all in a days work! I think the resulting images looked great and no one would ever guess they had such a story behind them! Well done.

Rebecca Marshall

Jan 31, 2018 at 9:10 pm

Thanks Nadia. I’m glad you found it interesting!