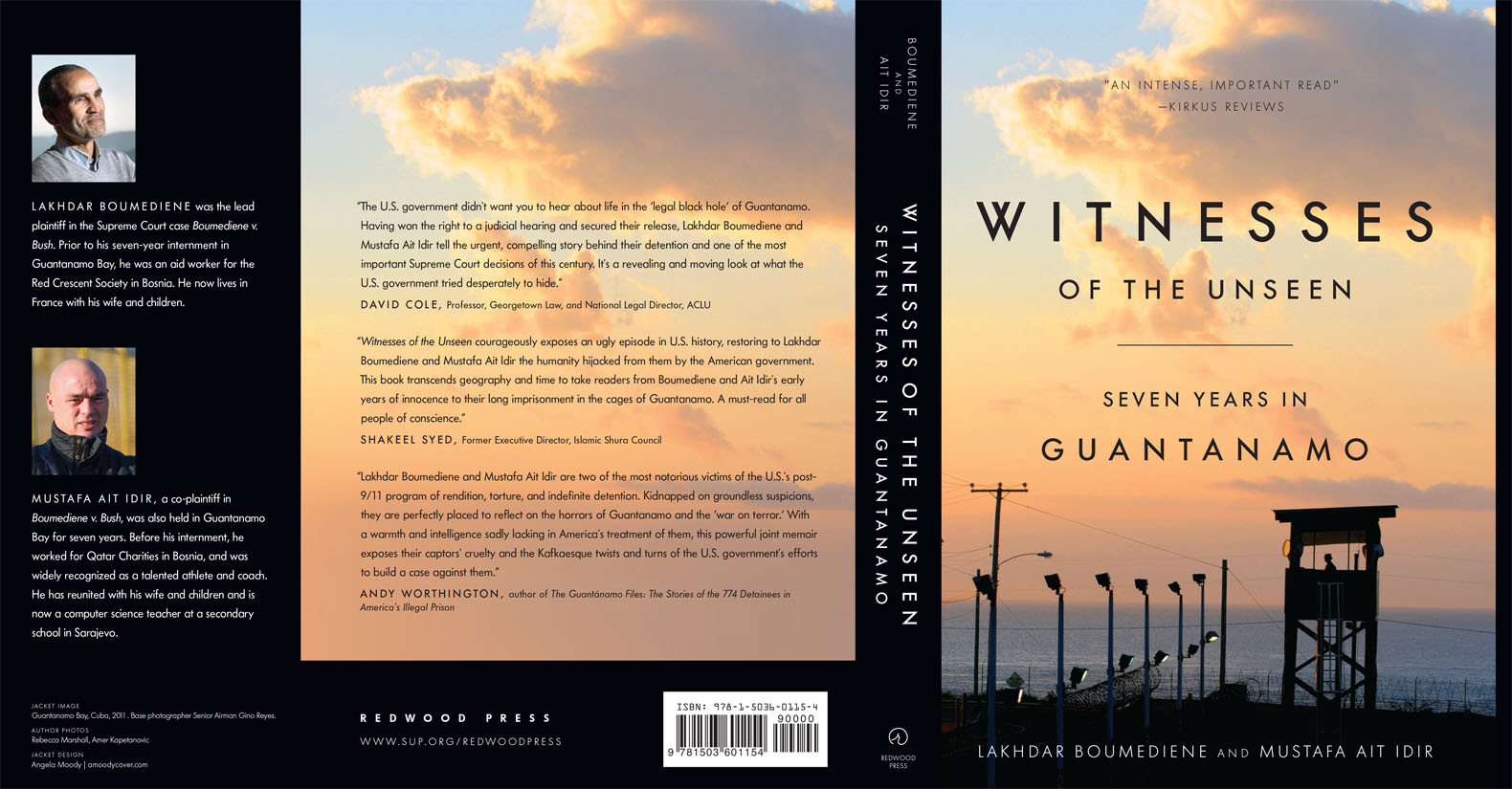

With the possible exception of events like the Monaco Grand Prix and the Cannes Film Festival, the French Riviera is not all about playboys and celebrities. One of the privileges of being a photographer in the South of France is the variety of people that I get to meet through my assignments. Early this year, I took a portrait of a man who lives a simple, anonymous life, in the hills above Nice. He has children, enjoys gardening, and likes quietly watching the world go by from the terrace of his local café. Yet few of his neighbours know that his story has been told in the international press, and he is now the subject of a book. Prior to his arrival on the French Riviera, Lakhdar Boumediene spent 7 years incarcerated in Guantánamo Bay.

Dark paranoia

A couple of years before, a New York Times colleague had told me about a recent trip to Provence to meet someone who’d been imprisoned in Guantánamo and, on release, re-homed in France. It seemed that the story of Boumediene’s suffering, and the dark shadow that lurked behind his manifest paranoia, had particularly touched the journalist. I was told that Boumediene had avoided eye contact during the interview and shook a little as he spoke, apparently in fear that the writer may be an undercover CIA agent.

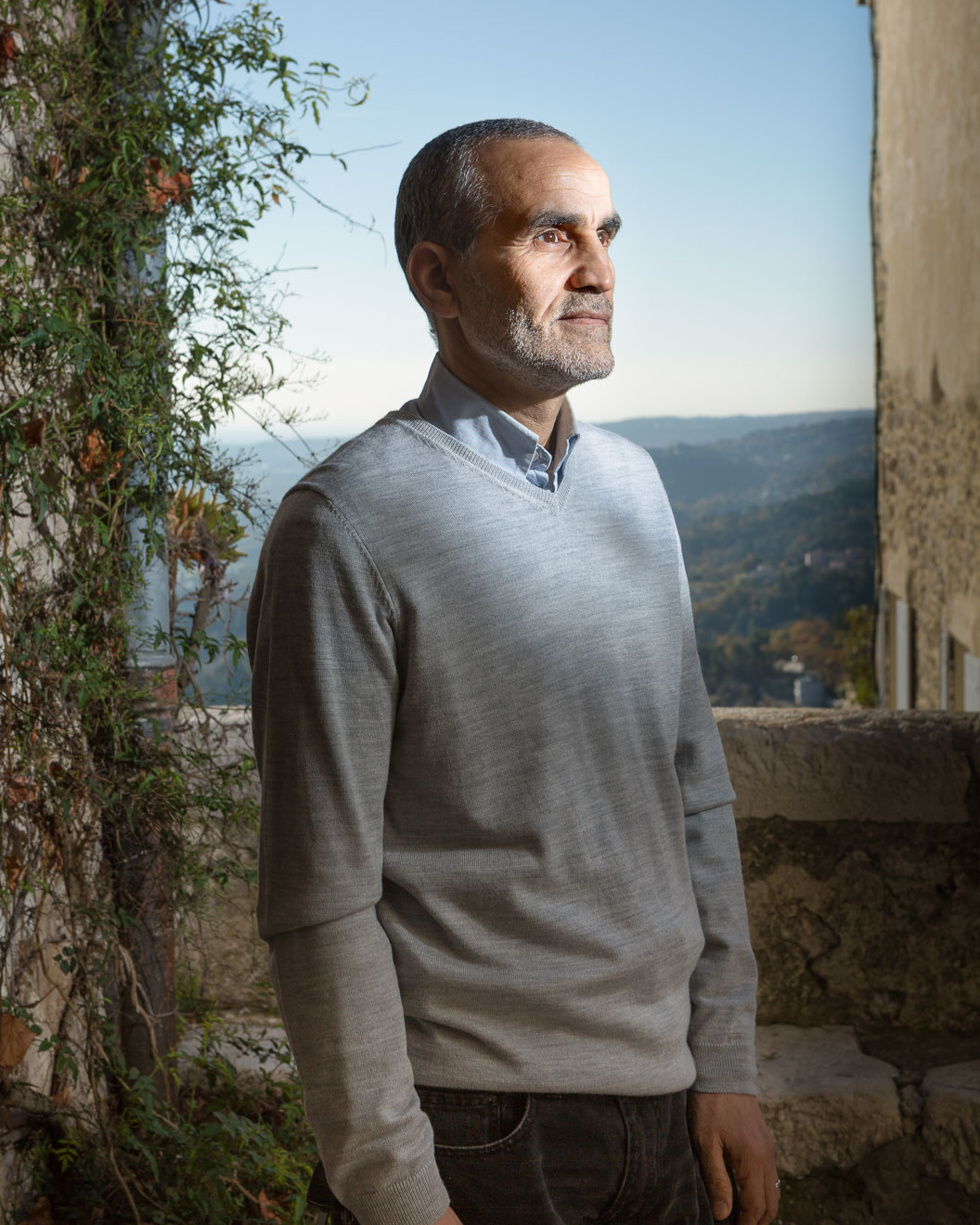

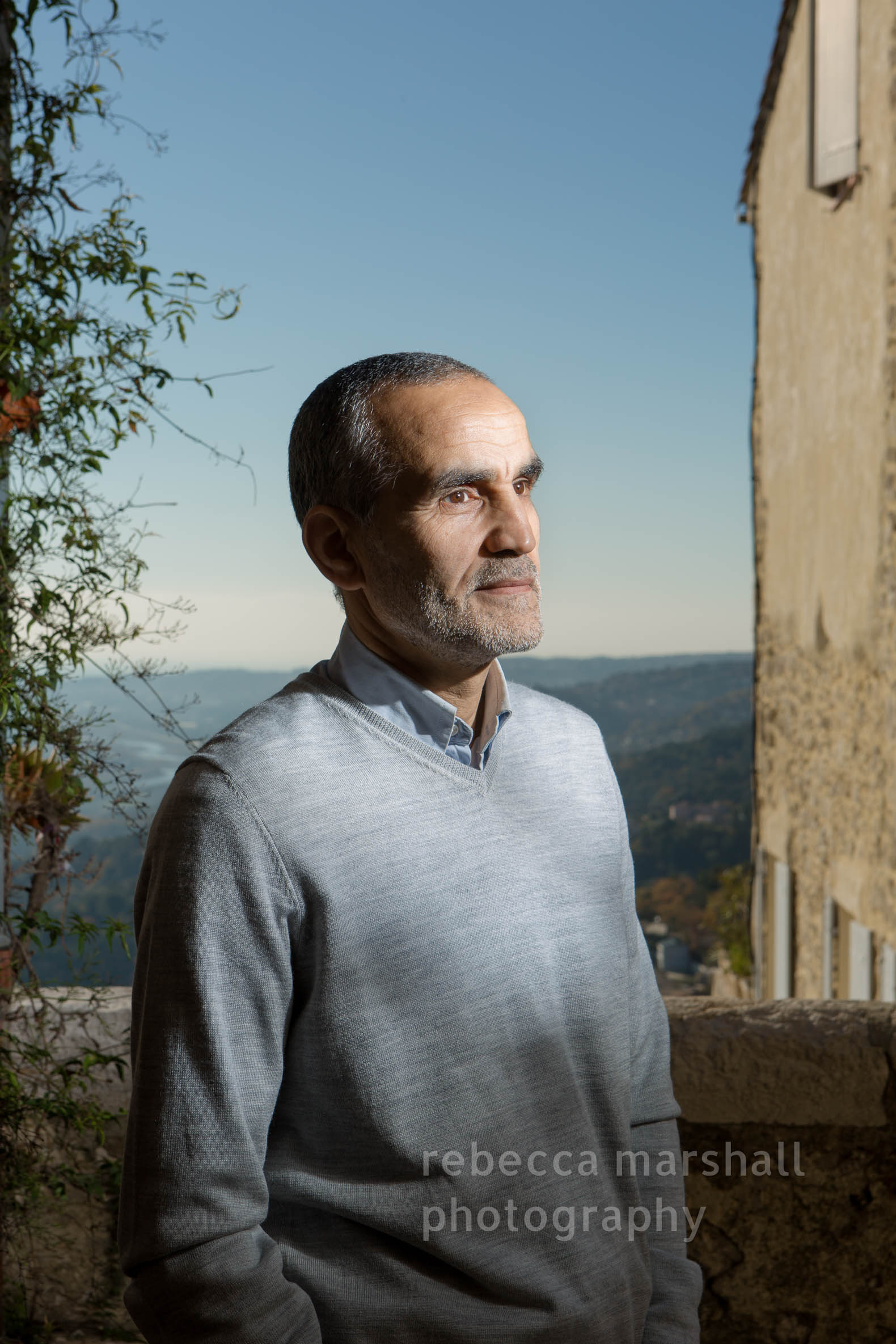

It was different when I was Boumediene’s photographer. Commissioned by Daniel Norland, co-author of Lakhdar’s memoir, to take a portrait for the book’s dust jacket, I figured CIA suspicions would be less likely to hang over me than a news journalist. However, I still felt this was someone who may need time to be at ease with a photographer and so, when we met, suggested that we begin with a coffee. Lakhdar tends not to speak of his time at Guantánamo and I did not raise the subject. Instead, with my assistant, Rebecca, we talked of the beauty of a nearby lake, discussed which vegetables were currently thriving, and chuckled at the bar’s aggressive chihuahua. By the time we walked up to the spots I’d chosen for his portrait, Lakhdar’s initial timidity had dissolved. He offered to carry my photographer’s bag (although it has wheels, he insisted on carrying it so as not wake the neighbours) and asked interestedly how my flash trigger worked.

High above the French Riviera

The winter light was sharp in the quiet streets of the medieval, hilltop village of Carros. Ancient, stark doorways and narrow alleyways in deep shadow beckoned left and right. If rare passers-by wondered why a photographer and her assistant were making portraits of this unassuming, 46 year-old Algerian man in such an out-of-the-way corner of Provence, no-one asked.

In the end, the portrait that was selected for the book was one of the first that I took, against a blue sky and view that blurred into distant Nice and the French Riviera. Daniel had wished me, as photographer, to capture the kindness and hope that he knows in Lakhdar – not simply to make a portrait of a victim. Indeed, as I worked, I noticed that despite the traces of suffering evident in his features, Lakhdar’s face, at certain moments, shone with a gentleness, openness and strength that I found humbling.

Going home to his wife…for 7 years

The facts that are known about Boumediene’s story are easily accessible online. In 2001, amid post-9/11 panic, Lakhdar, then an aid worker, had been leaving a courthouse in Bosnia a free man. He had just been tried by a Bosnian court on direct request by the Americans for allegedly planning to bomb the American Embassy in Sarajevo, but the judge had found him not guilty, based on a lack of evidence. As Lakhdar stepped outside, he felt relieved, keen to get home and tell his wife and two young daughters the good news. However, when he reached the bottom of the courthouse steps, a group of American soldiers sprang on him, threw a black bag over his head and bundled him into a van.

The next thing Lakhdar knew, he was in a cage in Guantánamo. For the next 7 years, he was kept in solitary confinement, shackled, regularly interrogated and tortured, unable to communicate with his wife, and given no explanation for his incarceration. Early on during his confinement, one interrogator even confessed to Lakhdar that his colleagues were sure he was no terrorist, but that didn’t matter. It wasn’t until 2008 that he had a chance to argue his innocence. Boumediene’s lawyers sued the federal government in a case “Boumediene v. Bush” that went all the way to the Supreme Court. Its landmark ruling established the right of Guantánamo detainees to use American courts to challenge their captivity, and Lakhdar’s release was ordered.

Shortly afterwards, he was sent to France (he has a sister-in-law living in Nice). France, however, has not granted him citizenship (and his Algerian and Bosnian passports, misplaced by the American authorities, have not been re-issued) and so he lives at the whim of authorities. Lakhdar has been looking for work for years unsuccessfully. A modest sum of money arrives every month in his bank account and pays his bills. But neither he, nor his lawyers, know where the money comes from.

Learning to walk again

The contrasts between a South of France village and Guantánamo Bay prison must be phenomenal. I found it unsurprising that Lakhdar seeks normalcy, and generally chooses not to discuss his time there. Content with my photographer’s research prior to the shoot and happy with the portraits, I asked if my companions wanted to sit down and have a soft drink before we parted. As we sat in the winter sunshine, a pleasant tiredness seemed to settle over us. Then suddenly, unprompted, Lakhdar, began to speak.

Clouds gathered over his face as Lakhdar transported us to his Guantánamo past. Reading about the facts beforehand had been one thing; being with him in person as he described his experience was quite another. Rebecca and I were very, very quiet as we listened, quiet as I drove her home afterwards, and still quiet after that. This is a man who could not walk when he was released and had to learn to walk again, after years in heavy chains. His wrists are still scarred from handcuffs. He spent his last 2 years in prison being force-fed through a broken nose while on hunger strike. Escorted out of his cell once a day, which was freezing in winter and scorching hot in the Cuban summer, he was taken for a few short minutes into a small, high-walled yard for fresh air. If, when being escorted down the corridor he said as much as “Hello” to another inmate, he was taken directly back to his solitary cell and punished. The worst of it all, he told us, the hardest thing to come to terms with even today, is that he still has no idea why he was put there. Even the court case that saw him released did not enable the confidential details of his case to be shared.

I saw Lakhdar just once after that. We met in Vence, the small town above the French Riviera where I live, and chatted for a while, absorbing a few rays of sunshine together. When we parted company, I lingered, and watched his figure slowly recede from view. As he melted away into the market day crowd, Lakhdar became just another French resident, on his quest for a baguette and some fresh tomatoes…

L.A.

Feb 2, 2018 at 1:01 pm

Thank YOU, Rebecca, for this.

And please, Thank Lakhdar, for not losing his humanity. He has my respect & my gratitude for his bravery to carry on & for standing up the the Supreme Court with the power of his innocence & winning! I feel so worthless, though, that I cannot do anything to help him now, nor can I erase what was done. I only have the hope that someday soon things will get better.

Rebecca Marshall

Feb 2, 2018 at 3:02 pm

I appreciate your appreciation of this post and your heartfelt comments, as I’m sure Lakhdar will.

Martin Gugino

Jun 1, 2018 at 10:15 am

This is so distressful. This is so distressful. It makes me look back into history to see when the US first left the track. That just makes it worse.