A mere 30-minute drive from France, on a hilltop high above the Italian Riviera, lies a rather unusual village. Located at the end of a long, winding road, this sleepy, medieval bourg is home to little over 300 people and looks like countless others in Italy or the neighbouring South of France. Yet it is a one-off, both in historical and contemporary terms, and has garnered more than its fair share of international press interest. This is more than just a village: it is a micronation, proclaiming independence from Italy. I recently had a somewhat unique photographer assignment here; one that included portraits of sect leaders, knights and a princess…

A princely monk and hidden treasure

Seborga’s claims to independence from Italy are fairly recent. Its first head of state was elected in the 1960s and Seborgans voted for independence from Italy just over 20 years ago, in a referendum that remains entirely ignored by the Italian government. However, being somewhat different is nothing new to Seborga.

Once land owned by monks (a fact that it shares with its near-neighbour Monaco), the commune of Seborga was home to a 10th century abbot who, rather unusually, managed to get himself additionally elected ‘Sovereign Prince’. Thus recognised as an independent principality by the Holy Roman Empire (some say it was the first constitutional monarchy in the world), Seborga was then, much later, completely omitted in 18th century papers covering the sale of swathes of land from Savoy to Italy. Indeed, this legal loophole is the pillar upon which the current claim to independence is based.

Seborga also boasts a long history interwoven with the Knights Templar. In the 12th century, 9 Knights of the Templar were ordained here, and it was from Seborga that they left for, and returned from, the Crusades. If you listen hard enough, you might catch a whisper in the dark alleyways of this village that the Templars once hid something here, the eponymous ‘Great Secret of Seborga‘. Whether this was a spiritual message, King Solomon’s bones or the Holy Grail remains unclear, but the stories don’t seem to have done any harm. Seborga’s tiny home-made sentry border control post is often empty, but plenty of tourists pass by during the summer season. The local shop sells a wide range of souvenirs (tourist passports, license plates, stamps and flags), on whose proceeds the Seborgans dutifully pay their taxes to Italy.

New arrivals, new secrets

However, the Financial Times didn’t send a photographer and writer to Seborga to investigate its history. No, we were here to investigate a new arrival to Seborga, yet another source of local intrigue.

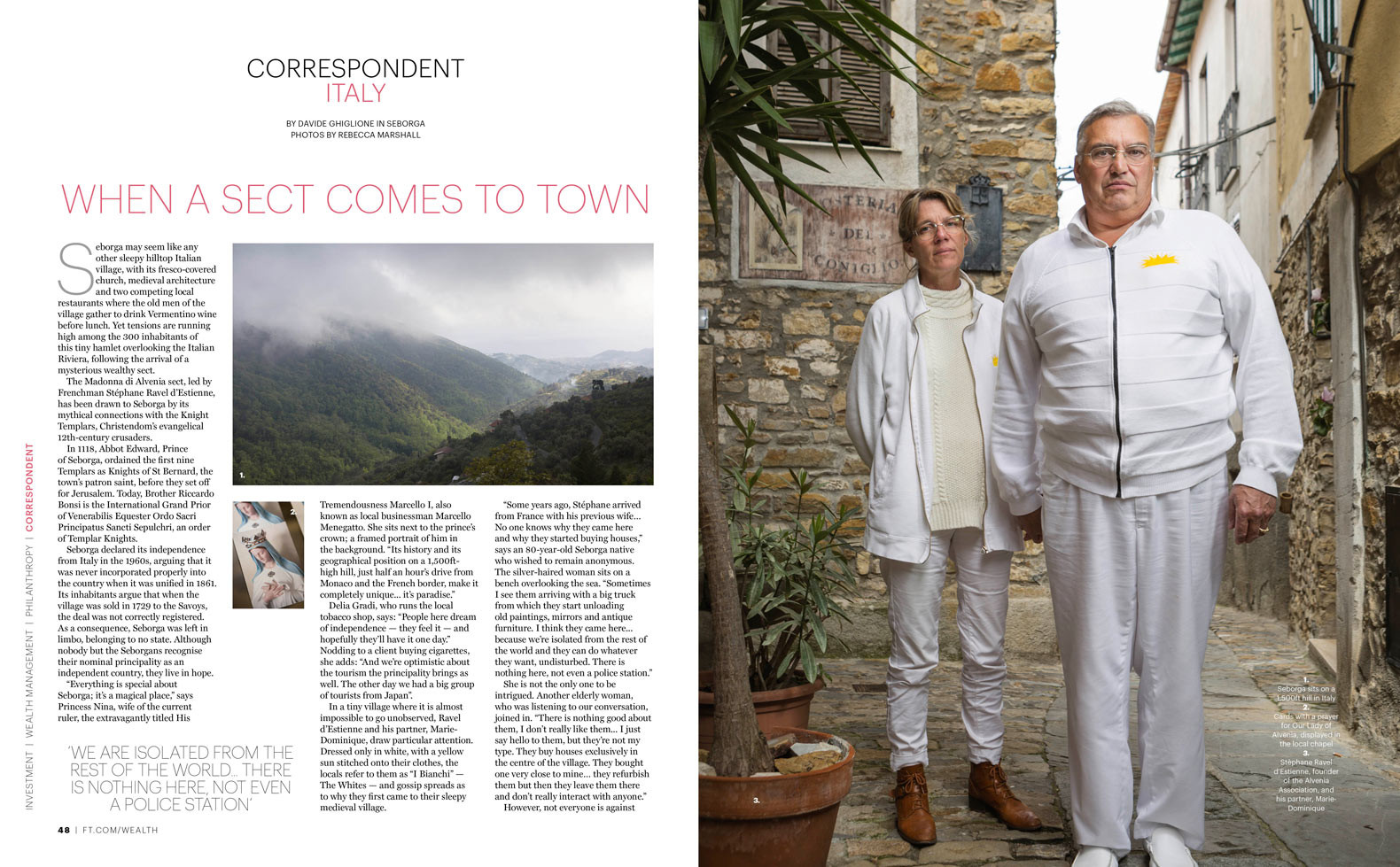

The French organisation Madonna di Alvenia, a mysterious religious sect (about which little published information is available since the French authorities removed their website), has recently made Seborga its headquarters. Its members are few (founder Stéphane Ravel d’Estienne and his partner Marie-Dominique are the only ones living in the village), but their impact on Seborga has been considerable. Locally known as ‘i Bianchi‘ [‘the Whites’], as they wear all white, the sect leaders have been on a mission, slowly but surely buying up a considerable number of houses in the village centre. They buy and they furnish, but they leave the properties empty. No-one knows why.

Devil’s spawn and an uneasy chair

When I arrived in Seborga, after a short drive from the South of France, journalist Davide appeared relieved that the photographer had showed up. It hadn’t been hard for him to find the villa belonging to Ravel d’Estienne the day before (freshly decorated in white, flying a large flag of the group’s logo, a yellow sun) and, on knocking, the writer had been welcomed inside for an interview that I don’t think he had expected to be granted. Davide had already been privy to wild local whispers of witchcraft, claims that one of the visiting members made pregnant by a villager is now carrying the antichrist and rumours that Ravel d’Estienne’s former wife was subject to a rather unusual death rite. According to stories, after her death she was left for 3 days in an armchair, in waiting for a resurrection that never came. Unfortunately, during the interview with Ravel d’Estienne in the lounge, Davide had gleaned that he was perhaps sitting in the selfsame chair that had hosted the inanimate ex-wife, and he’d not slept easy that night.

Houses for the children

Still, a new day had dawned, and, it being necessary to go back with a photographer for portraits, Davide conducted part II of his interview. This time, to his relief, they talked in the home office. As I assessed the light from antique lamps, considered the reflections I could see in the highly-polished Beckstein grand piano and wondered whether we’d be able to lift the gilded Louis XV-style desk, I half-listened to this former doctor talk. Ravel d’Estienne apparently has something of a hotline to God, and is on a basic mission to reveal spiritual treasure and predict the rebirth of the world.

Reluctant to deviate from this topic when asked the prosaic question of why he was buying up so much property, he gave a short answer “The purchase of the houses is nothing to do with Madonna di Alvenia: my partner and I have 9 children between us and we want them to come and stay”. Davide tested out one local’s claim that they were selecting property that was located in ‘spiritually important locations’ (on energy lines? in sites of ancient village entrances?), but it was quickly dismissed.

Nonetheless, I left fairly unconvinced that his answer justified the recent purchases of 18 separate houses (according to official records), one of which has been converted into a small, windowless chapel.

“We go to war”

The village’s only estate agent (and wife of the Minister of the Interior) did little to shed new light on the situation. She immediately became flustered when we announced ourselves as photographer and journalist. Before a single question had been asked, she blurted out that “Everything they’re doing is legal”, before saying that Ravel d’Estienne has only bought 11 properties in Seborga anyway and declining to say anything further. She was not alone: the majority of villagers refused to speak to us, let alone grant a photographer a portrait. Some appeared fearful, even: one woman explained apologetically “I’ve got a young child, I just can’t afford to take the risk of talking to you“.

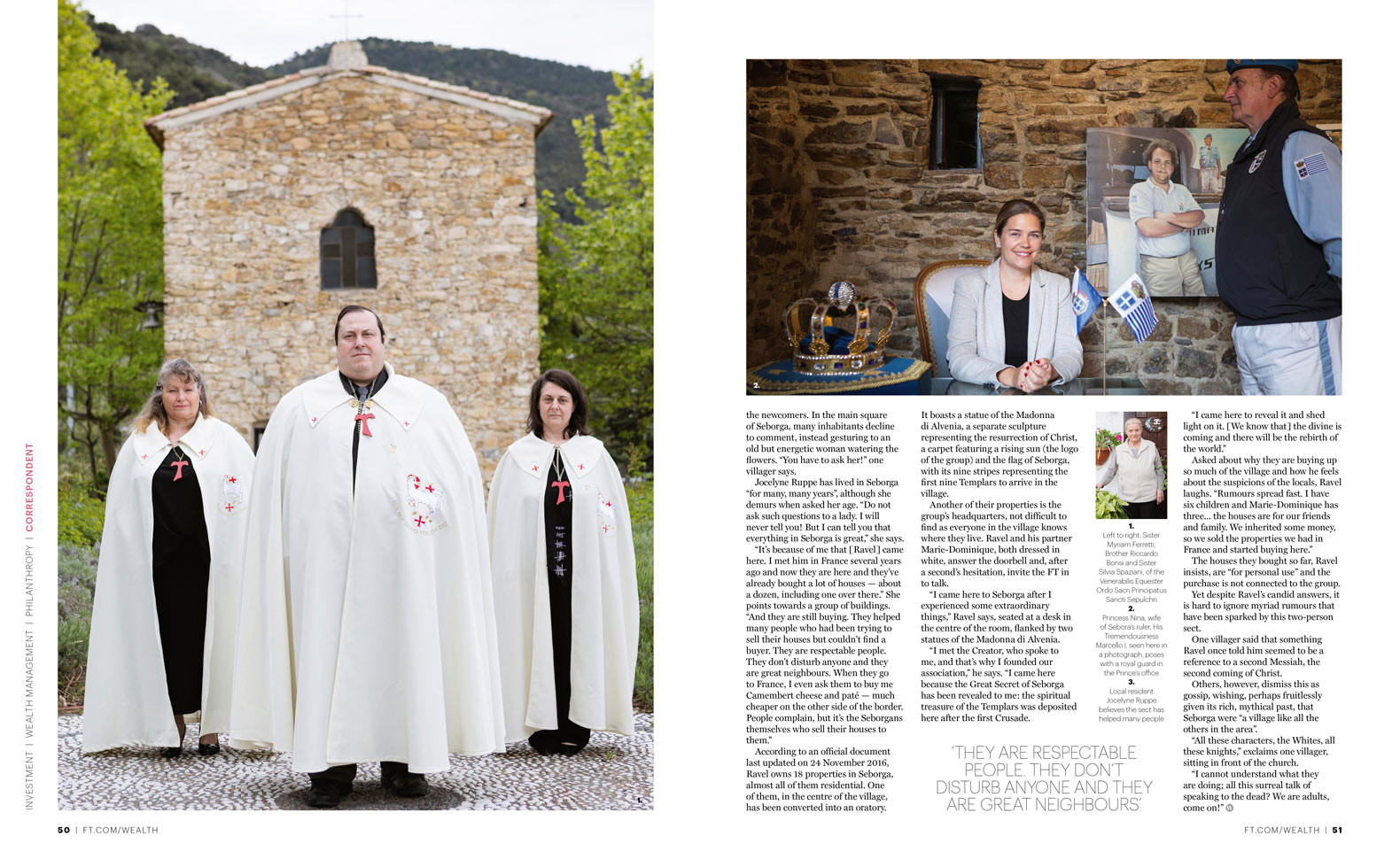

Even if they weren’t the focus of the article, one group, however, really did want to talk to us. We had no idea how they knew we were in town but, during the day, representatives of various orders of the Knights Templar kept showing up unexpectedly, cloaked in an air of mystery. Easing themselves out of a battered saloon car, one group of three Knights arrived after lunch, in full regalia, ready for the portrait photographer. Taking a tentative first step in trying to understand the Knights phenomenon, I asked Brother Riccardo Bonsi of the Venerabilis Equester Ordo Sacri Principatus Sancti Sepulchri what made his particular order different from the others. He responded fiercely: “We go to war. We are Knights of Combat”. Weighing in at at least 130 kilos, he didn’t look especially ready for physical combat, so I assumed his meaning was metaphorical – but remained unclear who the enemy was.

Even Princess Nina, wife of Seborga’s recently crowned prince, His Tremendousness Marcello I, was a closed book, both about the Property Mystery and the Knights. Posing beside the crown with a uniformed royal guard, she had been very happy to talk about Seborga’s beauty, and gush that “Everyone loves a fairytale princess”, but her brow darkened when asked a general question about the Knights Templar. “I can’t talk about the Knights, it’s complicated”.

It seems that in Seborga, much is complicated.