The phone call came out of the blue one evening. “Is this Rebecca Marshall, South of France photographer? I would like to invite you to Russia“. The 2016 edition of Uglich Photo Parade, one of Russia’s most prominent annual photo festivals, was being planned. With ‘France’ one of its themes, organiser Yuliya was looking for a France-based photographer to give a workshop. So it was that I set off on an unexpected adventure that was to involve food and travel photography, street portraits, a fierce bull, elk ticks and space cheese.

Famous food photographer from France

It was touch and go whether I’d get my visa, right up until the day before my flight. Due to the terror attack in Nice, the Russian Embassy here had remained closed and its neighbour in Marseille was thoroughly over-subscribed. I discovered that it is surprisingly difficult to get Russian doors opened in a hurry, especially for a British photographer living in France. Still, on 10th August, I found myself on the five hour drive northwards from Moscow to reach Uglich, a pretty little town nestled beside the Volga river. Fortunately I was met on arrival by an interpreter, the delightful Lera: pretty much the only word I knew in Russian was ‘raspberry‘, and while this knowledge had been a kind contribution by Russian clients back on the French Riviera, it would clearly be of limited value for any prolonged stay in the country.

Uglich was buzzing. Hundreds of photographers, professional and amateur, had come from all over Russia to see the exhibitions and participate in photographic activities. My involvement during the event, more extensive than I had realised, began with a one hour presentation of my work as photographer in the South of France, to a packed lecture theatre. Apart from the food photography workshop, I was also asked to guide two other reportage photography ‘masterclasses’, give portfolio reviews, judge prize winners and present prizes on stage at the closing ceremony. I was amused to discover that Yuliya had found me by typing ‘famous food photographer France‘ into Google, and that this deed had apparently made me so. During the festival, several Russian TV and radio stations interviewed me and it is the only time that I have ever experienced being accosted in the street for my autograph.

Communist cows and jewellery for cakes

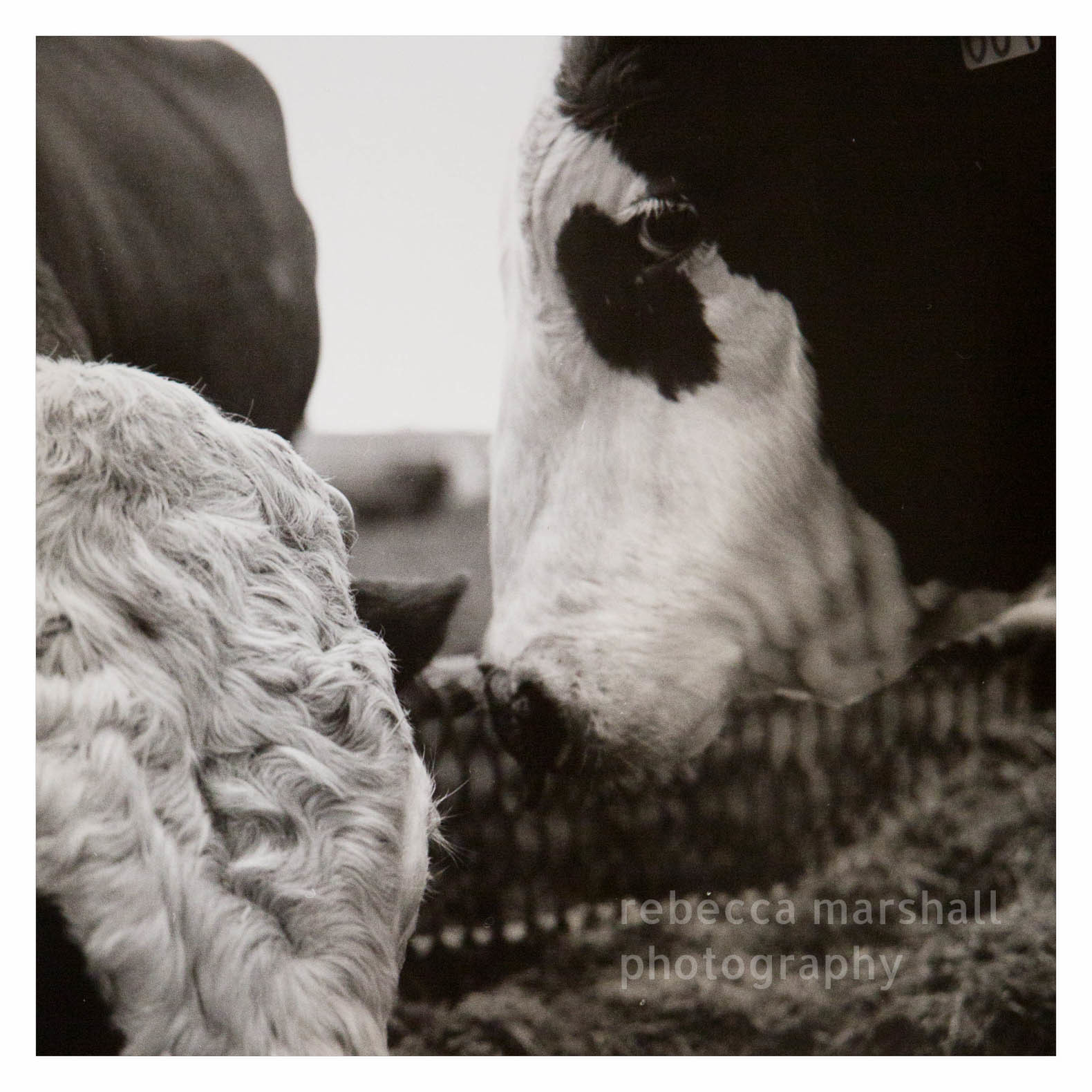

Early in the morning of my workshop, Lera appeared on my path to the breakfast room to inform me that a car was waiting for us outside. An impromptu visit had been organised last minute to Russia’s first certified organic farm (the sponsor of my trip). Slightly preoccupied by my empty stomach and the rapidly diminishing time remaining before the workshop began, I went to meet the cows that had supplied some of the ingredients I would very soon be working with. I came eye to eye with a ferocious-looking bull, admired the self-milking machines that 200 cows use, one-by-one, of their own accord (‘no problem: they’re good, communist-spirit cows‘, quipped the farm manager) and envied the massage machines available on tap for these lucky bovines.

By the time I got back to town, I was feeling slightly light-headed. But there was no time to address my hunger: the 40-or-so delegates were already waiting expectantly in the hotel restaurant where my workshop was due to begin. Thanks to the monthly photography class that I give in the South of France, I felt fairly comfortable teaching, but unforeseen challenges nonetheless arose. Having planned to use the bright terrace outside for some practical work, I hadn’t counted on the clouds of wasps that prevent anyone with food or drinks venturing beyond the dark lounge. Halfway through my presentation, there was a change of interpreter, the replacement speaking only French, so I had to abruptly change the language of delivery, translating my notes. as I went. Asking chefs in France to explain their creations is generally an informative exercise, but here the timid hotel chefs were almost entirely mute when I asked them to tell everyone what dishes they were presenting. And discussions around food styling were in some cases interpreted in unexpected ways (jewellery and sequins were suggested to decorate a cake; parsley to garnish sweet buns).

But, once the work was underway, I glanced away from the TV journalist interviewing me towards the hive of activity in the room. Everywhere people were climbing on furniture, waving reflectors, pointing cameras, rushing around with various piles of ingredients, talking heatedly and directing one another in their work groups. I figured things were on track. At the end, as I finally fell upon an abandoned cottage cheese cake, Yuliya pronounced it the coolest workshop she’d ever seen (before we established it was the only one she’d actually attended). Forward to 2:19 on this Russian state TV clip to see my interview and the workshop in full flow.

Pickled herring in a fur coat

During my week, I certainly made the most of opportunities to sample Russian cuisine, from the intriguingly-named ‘pickled herring in a fur coat‘ to the delights of horseradish vodka. I also had, more than once, the extraordinary experience of ordering a set menu in a restaurant, only to have everything arrive at once (starter, mains, dessert and coffee included).

The reportage classes I gave took me to Uglich’s annual harvest fair (where I saw an impressive life-size penguin carved from a marrow and some carrots) and to a luxury lakeside resort nearby, which felt a little familiar – a French Riviera vibe in the rural heart of Russia. Here, at a special ‘salon de la gastronomie‘, I was invited to taste artisan cheeses and astonishingly good Russian wines (quality Pinot Noir and other Crimean-grown wines being part of a new and trendy native wine scene). Here, the MC suddenly stopped the live band and put a microphone into my hand for an impromptu speech; shortly afterwards a TV camera followed me outside, my arms full of the wine that had just been presented to me, for another interview. I suspect that my words were a little more vacuous this time…

Space cheese institute

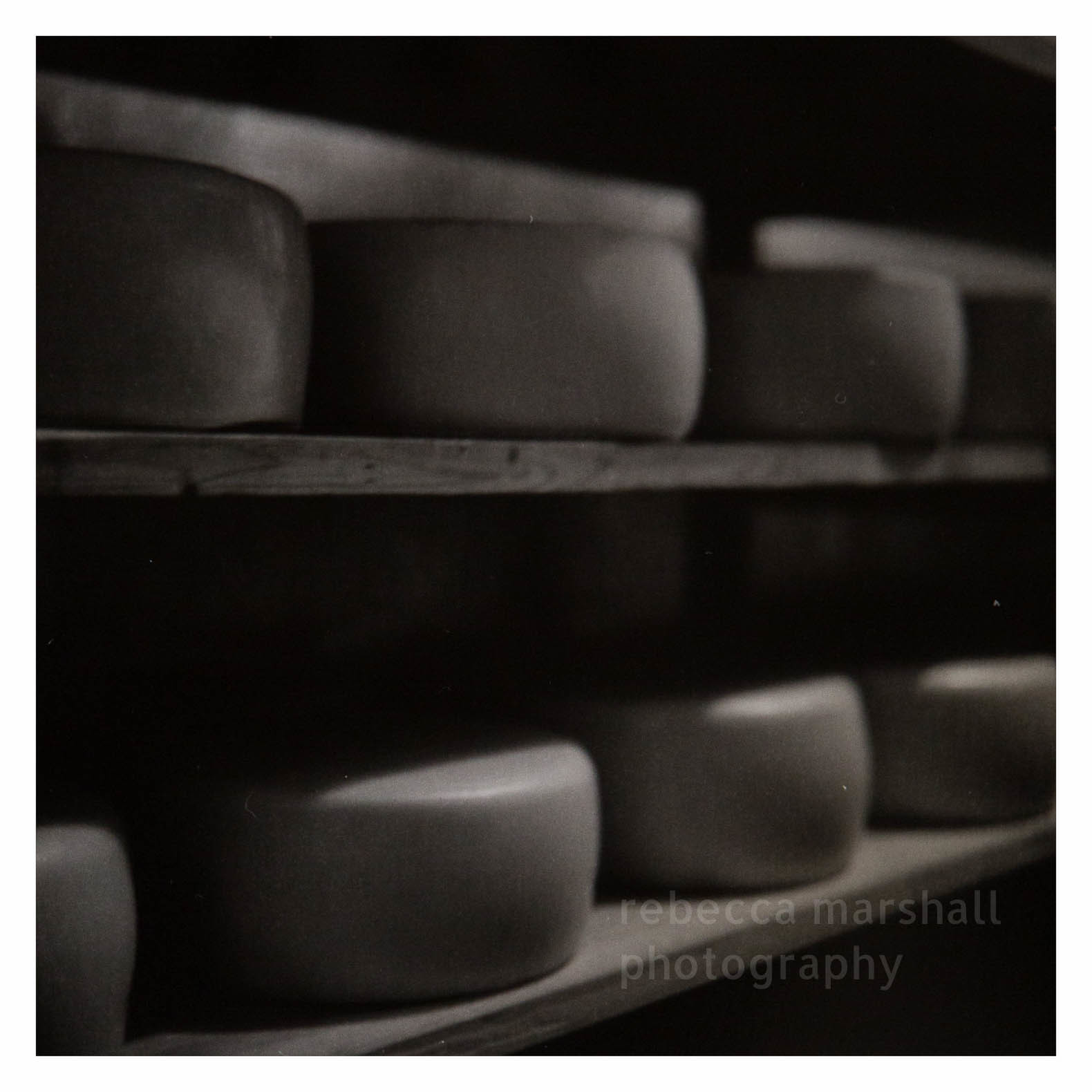

At the end of the festival, I had just a little time to myself. Much to Yuliya’s surprise, who had planned a last day’s guided tour of Moscow’s sights for the few visiting foreign photographers, I opted to stay in Uglich. Over borscht and vodka one night, having exhausted discussion about local points of pride (the hydroelectric dam which remained undestroyed by Germans during the war, the Museum of Prison Art displaying somewhat depressing paintings made by prisoners with limited means – such as the portrait of a inmate’s lover painted in cigarette ash, the church built on the spot where Ivan the Terrible’s youngest son was murdered), someone mentioned Uglich’s reputed institute for cheese-making bacteria. Sorry? My ears immediately pricked up. Here, scientists had allegedly made the cheese that Russian astronauts took with them on space missions. The building, hidden in the trees on the outskirts of town, is closed to outsiders, but I asked Yuliya is she could work her magic to get me a visit, and work her magic she did.

The Russian Research Institute for Butter and Cheese Making, founded in 1944, was once the pride and joy of cheese-makers. Back in the 1930s, the only cheese to be found in Russia was cottage cheese, made by peasants in certain regions for their own consumption, but the Institute set out to change all that. Here, scientists led a brave new project to give birth to a national cheese industry. Worlds apart from the artisan cheeses I’d tasted a short time before, the focus was on quantity and consistency: industrialising cheese for the Russian nation. Here, cheese-making regulations were established, cheese factories were equipped and their personnel trained, new cheeses for pizza, sausage-like cheeses and sweet cheese for chocolate desserts were concocted – indeed, several of Russia’s most famous cheeses were invented in Uglich. But by far their most curious mission had been to make cheese for trips to space, in the 1970s and 80s. The Department of Soft Cheeses met the challenge of making a product which would survive the special extra-terrestrial conditions, using higher temperatures than usual to heat the rennet, and sealing packets hermetically.

Today, the quiet building and much of its equipment looks like a time capsule to the glory days of the Soviet Union. They are no longer sending cheese to the moon and I didn’t see evidence of much current invention, but there was a certain beauty to the place. I had only an analogue Rolleiflex with me, and the roll of black and white low-speed film I had loaded was challenging to use in the dark spaces of the building, but the camera’s age and quiet, slow operation blended in perfectly with the atmosphere.

Elk ticks and beavers

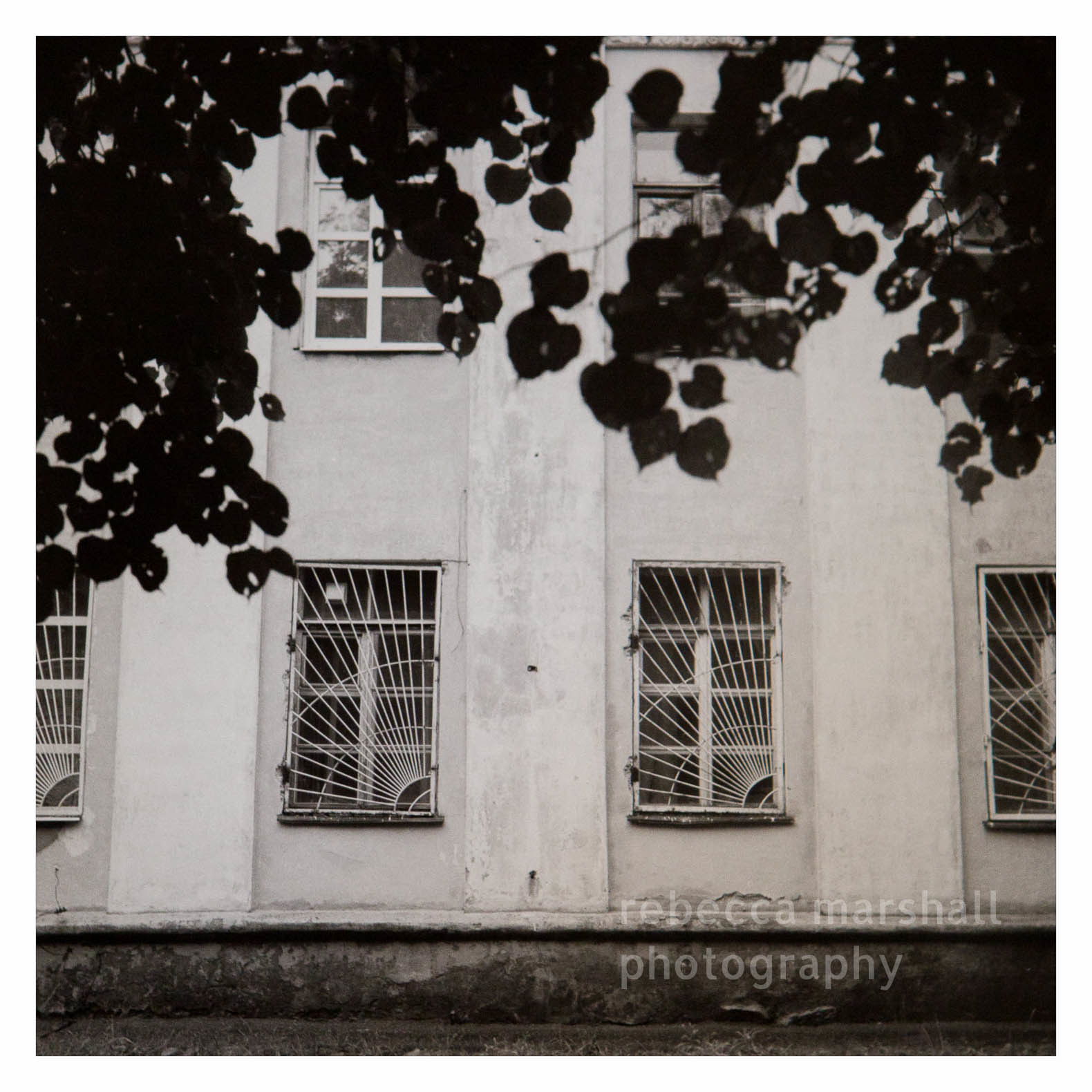

I did two other things while my photographer colleagues were off sightseeing in Moscow. The first was stepping out with Lera and my Rollei to explore the backstreets of Uglich. We followed our noses along roads that even Lera, in her home town, had never ventured down. In the warm summer sun, we drank in the beauty of the little wooden houses and the riots of colour in the half-wild gardens spread out before them. It was Sunday and many people were out and about, tending to their plants and animals. Thanks to Lera’s introduction, I took some portraits along the way.

The second thing I did was to ditch my camera and go careering through the seemingly endless, wild forest that surrounds Uglich, on horseback. I didn’t catch sight of any of the bears I had been told about, but I did see a dam that had been built by beavers, and I also experienced the novelty of being bombarded by elk ticks. Enormous, soft, black creatures, they are ticks on steroids. Fortunately, they don’t bite humans but they proved very difficult to disentangle. Over the hours that followed, I took to obsessively running my fingers through my hair, and picked out more ticks than felt comfortable.

When at last I left, Russia didn’t appear to want to let me go, setting miles and miles of solid traffic jams ahead on the road back to the airport. As I burst out of the taxi and raced to the boarding gate, catching my flight by an elk’s whisker, I felt my departure was somewhat premature. I considered my greatly expanded vocabulary (which now includes the words ‘beaver‘, ‘owl‘ and a bizarre tongue twister) and my new-found taste for borscht, and I decided that I am now rather well-equipped to travel back and continue my discovery of this intriguing land. Watch this space…